This is the sixth installment in a series of interviews with scholars and experts on China as a resurgent Asian power that is changing the regional order. This installment looks into the intensifying Sino-U.S. rivalry and China’s revisionism. — Ed.

China and the U.S. have been restraining themselves to conserve their strength, as they are caught in a long-term geopolitical rivalry, French China expert Francois Godement said, noting the limitation of conflict is the “main zone of bilateral cooperation.” During an interview with The Korea Herald, the scholar also underscored the need for the two powers to “make adjustments” in their external policies to promote stability and prevent needless conflicts.

During an interview with The Korea Herald, the scholar also underscored the need for the two powers to “make adjustments” in their external policies to promote stability and prevent needless conflicts.

“For the U.S., promoting international legality in the geopolitical arena should be matched with acceptance for more representation of China and other major emerging countries in international economic institutions,” he said.

“For China, it should demonstrate that it is not promoting a return to the ‘sphere of influence’ geopolitics that has always resulted in major conflicts in the past.”

Touching on the widespread geopolitical interpretation of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, which observers say could challenge the U.S.-led institutions such as the World Bank, he said the alleged risks were “vastly exaggerated.”

“The AIIB has been designed almost as a business school case study — a model whereby China can transfer management recipes from international institutions. And it is one in a gamut of Chinese funds active in the One Belt One Road initiative, for example,” he said.

“A much more consistent challenge is the rise of financing completely outside international institutions — commercial and tied aid through bilateral relations with complete opacity, but with resources that dwarf those of existing international institutions.”

As for Beijing’s hopes to realize its one-China dream, he said “fast” reunification may be unlikely.

“Politically, it (Taiwan) is one of the world’s liveliest democracies — the risks of absorption in China’s top-down system are huge, as even the much more muted Hong Kong model demonstrates,” he said.

“Political change in the mainland is the key, but it is as of yet unpredictable. Meanwhile, avoiding provocations on both sides seems to be the essence of wisdom.”

The following is the full interview with Godement.

Korea Herald: Chinese leader Xi Jinping has talked about his government’s main objective — the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. What does this mean? How do you think Xi has been pushing to achieve that objective so far?

Francois Godement: The “rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation, and the “China dream,” an expression that he also uses, are each interesting in their own way. “Rejuvenation” is a paradoxical term when population aging is actually looming ahead for China, with all its predictable economic and social consequences. And the past decades have been a period of extraordinary dynamism — it is hard to see how China’s tempo could accelerate further.

But what Xi Jinping means is going back to the roots of China’s historical greatness, and reclaiming them. This is a wider basis for legitimacy than Communist ideology, although of course Mr. Xi is also a staunch defender of the party. “Rejuvenation” also implies that China’s international standing was greater in the distant past, and that this position must be reclaimed. This is a conservative dictum — quite close to the “restoration” (tongzhi) ideal of mid-19th century China.

The “China dream,” less used recently, is an apposite dictum. First, it is a take on the “American dream,” and in both cases, the expression looks to the future rather than to the past. In his first speech when Mr. Xi was designated as China’s leader in 2012, he also extolled “people’s yearning for a good and beautiful life” and “happiness.” These terms, focused on the individual rather than on the collective, identify more with the French or American revolutions than with Leninism. Mr. Xi is pragmatic and diverse; he stands both for unabashed nationalism and for individual happiness.

KH: Do you regard China as a revisionist or status-quo power?

Godement: “The best defense is attack,” says an old French proverb. China’s economy may have boomed for almost four decades, but the regime feels threatened from the outside.

The fall of other socialist states in Europe, the attractiveness of political democracy, the “soft power” that is now further enhanced by the IT age and social media are indeed issues for the Chinese leadership. Chinese society is individualistic, porous and increasingly outward looking. It is after 1989 that nationalism has been revived, from enhanced territorial claims to historical grievances, including at all levels of education. “Revisionism” follows on, since it is basically a method to redress perceived grievances. As a mobilization tool to keep in line the population — especially the young — by emphasizing both grievances and lofty international goals, historical revisionism is effective.

There are, of course, more objective reasons for “revisionism.” The PRC (People’s Republic of China) was not a member of international institutions between 1949 and 1972. The Cold War ran on the supremacy of the U.S. and USSR. And when it ended, a short phase of U.S. leadership ensued.

Not only has the economy boomed for 37 years, but also China has consistently outstripped every other nation in terms of the military budget’s yearly increase. It is hard there to distinguish the consequence from the cause. China’s economy, based on huge savings and external surpluses, shielded by its developing economy status, allows for much influence. The mere existence of two sets of rules — one for developed economies, one for developing economies — becomes an international challenge once a developing economy — China — becomes the world’s second largest.

China navigates between these special advantages — including a semi-closed capital account, a quasi-pegged currency and very little regard for labor and union standards — and the realistic perception that if free trade, which has been very favorable to China, is to endure, then there have to be benefits for everybody. Hence the adoption by China of the “win-win” rhetoric once owned by the United States in the early 1990s. Hence also the push for inclusion in the IMF’s reserve currencies, and for market economy status. A booming export economy has a lot to lose from a breakdown in international economic institutions.

More broadly, China’s strategic culture has always been torn between a “soft power” line, where the mutual advantages of trade and interchange ensure Chinese influence, and a bellicose streak.

In geopolitical terms, China always advocates “stability” (by which it usually means a guarantee against regime change) but is not, or not yet, a status quo power. We can see that very clearly with territorial claims, but also with the reluctance to even state exactly what these claims are in many cases. A weaker China has signed up to many compromises in the past, (but) a stronger and ascending China finds it much harder to do so. This is in part because political leaders and activists could easily challenge one another on the basis of insufficient patriotism, and in another part because China’s rise is not finished and it is easy to guess that waiting, holding firm and wearing out opposing parties may produce better terms in the future. It is a thin line, but so far China has avoided the risk of any major conflict.

KH: Many have talked about a “power shift” in Asia that has been triggered by the rise of China. Do you think that a regional power shift is really taking place? What are its implications on the overall security and that of South Korea?

Godement: China’s march to the so-called regional hegemony is made of two trends. One is the anticipation by everyone of even more growth and capacities in the near future. If China’s military budget is already four times the ROK’s (Republic of Korea), and more than twice Japan’s, one can guess what will result in the future. But a military predominance (excluding the American balancer) could be matched by a consistent regional union based on democracy — one that would be open to China but mindful of rules and restraint. That is not the case. While it is fashionable to decry the European Union’s clumsiness and its inward-looking attention, it is either resisting shocks or absorbing them. Southeast Asia, beyond negative principles — conflict avoidance, nonintervention, and preference for consensus — has no integrative method, and little unity on sensitive issues. The return of historical issues in Northeast Asia — without ascribing responsibilities — has created a triangle where China, with a public opinion under control and a centralized political system, has a maneuvering advantage.

South Korea’s predicament is nothing new — even though it is dynamic, it is still the smaller fish. If we had a triangle of cooperation in Northeast Asia, South Korea would not have a bargaining advantage over the larger economies of China and Japan. If this is a competitive triangle, then it is tempting for South Korea to play a balancing role — in effect, trying to get more from one or the other. Yet two things appear clear: Korean reunification cannot happen without Chinese neutrality to the event, but China will not push for it.

KH: Xi has talked of a new type of great-power relations with the U.S. How do you think China will manage its relations with the U.S.?

Godement: There is no question that in spite of economic interdependence, the relationship is a competitive one for the foreseeable future. Both sides see threats to their role in the international order. China will no longer be contained, the United States will not give up its prevailing role in the international order. Both sides are in for the long haul — in fact, this may explain why the Obama administration has been so restrained in its military engagement around the globe, from Ukraine to Syria and Afghanistan. And why China has skirted actual regional conflicts, conserving its strength instead. The limitation of conflict is the main zone of cooperation, along with non-vital issues — climate and environment are one such example, just as an avoidance rule on terrorism: Neither side will hurt the other’s fight against terrorism, although they show little active support for one another.

Could economic interdependence change that? President Park Geun-hye has described “Asia’s paradox,” whereby geopolitical clashes challenge economic growth. In U.S.-China relations, could economic benefit contain the strategic competition? Both sides must make adjustments. For the U.S., promoting international legality in the geopolitical arena should be matched with acceptance of more representation of China and other major emerging countries in international economic institutions. For China, it should demonstrate that it is not promoting a return to the “sphere of influence” geopolitics that has always resulted in major conflicts in the past.

KH: The importance of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in terms of geopolitics seems to be growing particularly when the U.S.-China competition is intensifying. What do you think?

Godement: China will not “use ASEAN,” because that would imply that ASEAN has a unitary stance and can be swayed as a whole. Recent history demonstrates that it is far more easily divided, and that is a weakness that any realist diplomacy — but first of all China’s — can exploit easily. True, China has made ASEAN as a whole a “strategic partner,” but that is more a matter of avoiding polemics than of positive action. Trade bargaining has created some results: the ASEAN Free Trade Zone and now the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) project, but these are more superficial deals than either the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) or the FTA concluded by the EU with Korea, and perhaps at some point with Japan.

There is some U.S. responsibility, however, in the fraying of the regional order in Northeast and Southeast Asia. Following the adage that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” the U.S. has based much of its action on the transitory postwar order, conceived around hub-and-spoke alliances and with minimal attention to regional developments. There are now some adjustments with ASEAN and with the TPP. But by and large, the U.S. has acted as if the postwar order, based on a power balancer from outside the region, was eternal. The very successes of Asia challenge this view.

KH: Amid uncertainties over the regional security and order, some stress the need to build a multilateral security cooperation mechanism in Asia, just as Europe has done. Would it be possible to build such a mechanism?

Godement: I earlier regretted Asian division. But a grand scheme is not the way Asian history moves forward. We already have a surfeit of regional organizations, almost always with very limited common competences. Europe was built first among five, then seven, nine, 12, 15, 27 and 28 … What is much more important now for Asia is acceptance of existing international rules, of legal arbitration, and much more limited partnerships of cooperation. This is true above all of China, Korea and Japan — although a full resolution of issues cannot be made without Russia, and in practice without Taiwan. We need more resolution of territorial issues among ASEAN members. China, the Philippines and Vietnam are a dangerous triangle, even if they have at some point agreed on common offshore exploration — a development now well forgotten.

Sixty years after the first attempts at European defense, Europe is not fully capable of defending itself without a U.S.-NATO contribution. Defense is the last mutualized area in international integration processes. More limited steps — confidence building, conflict prevention and crisis mechanisms — are more realistic priorities for Asia. CSCAP (Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific) — in which both Korea and Europe have a hand — has started on that road, which appears to be a slow one.

KH: One crucial variable in China’s push for regional influence is Japan. What kind of a China-Japan relationship do you think China will pursue?

Godement: Here is real interdependence limiting conflict. Even after some recent diversification, Japan’s big companies depend on China’s factories and the Chinese market. Northeast China is deeply integrated into Japan’s production chain. This has literally obliterated the polemics about Japan’s external trade surplus, which has instead moved to China.

Adding to that, the absolute preference for peace of Japanese citizens is a huge restraining factor in a democracy. Even as relations with China have soured, this preference has not abated.

Fundamentally, Japan had turned down in the 1980s what could have been a deeper form of Asian integration around Japan’s powerhouse — a path divergent from the German case. And on defense issues, in spite of some debate Japan has been mostly reactive rather than proactive. Current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe must campaign hard to accomplish limited changes — this in the face of literally 17 years of Chinese polemics and incidents that abated only between 2006 and 2009. Broadly speaking, Japan competes with one hand tied behind its back, and this is still by consensus.

But the above applies to Japan. What about China? There is no doubt that there is a widely shared psychological of triumph in superseding Japan — in economic size, in military budget if not yet capacities, in international echo. Frequent changes of leadership in the Japanese democracy also convey a sense of either weakness, or vulnerability to Chinese leaders who stay on.

But if we do not believe Taiwan can be reunited under widely different systems, how could we believe that Japan could be Finlandized — e.g. relegated to quasi-neutrality with a defensive military force outside any alliance? Influence is one thing, and China has gained that over Japan (although one would be surprised by the practical results of many low-key Japanese international programs). Subjugation or dominance is another story, and realistic Chinese leaders must see this.

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

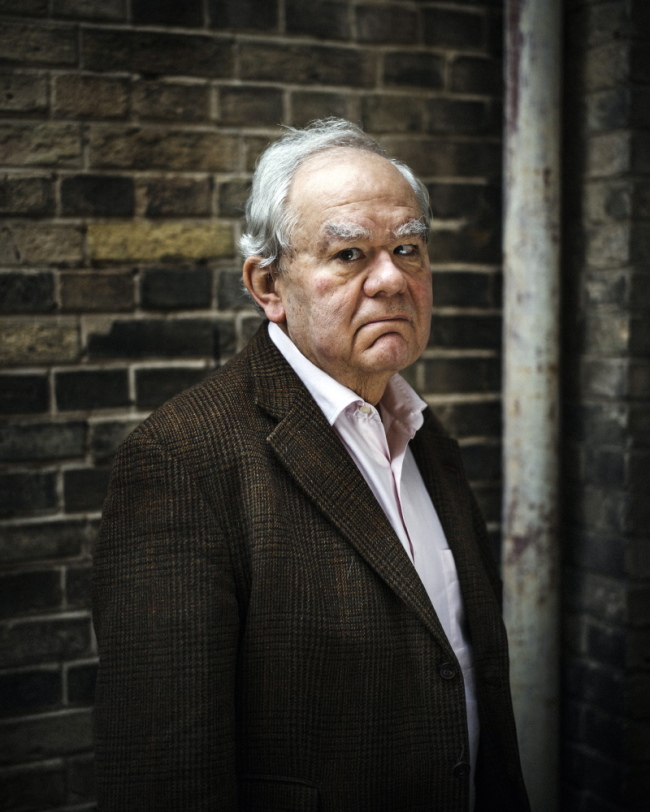

**Francois Godement

●Godement, the director of the Asia & China program of the European Council on Foreign Relations, is noted for his extensive research on Chinese and East Asian strategic and international affairs.

●He is a permanent external consultant to the Policy Planning Staff of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He has also served as a nonresident senior associate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

●He lectured as a professor at the National Oriental Institute in Paris from 1992-2006 and at Sciences Po from 2006-2014. He is the editor of China Analysis, an e-journal.

●He has authored a number of books and articles including “Contemporary China, from Mao to Market” (2015), “A Global China Policy” (2010), “Beyond Maastricht: a New Deal for the Eurozone” (2010), “China: the Scramble for Europe” (2011) and “France’s Pivot to Asia” (2014).

●He earned a history degree from the Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris, and was a postgraduate student at Harvard University.