This is the eighth installment in a series of interviews with scholars and experts on China as a resurgent Asian power that is changing the regional order. This installment looks into China’s military power vis-a-vis that of the U.S. Due to the depth and extent of areas covered in this installment, the interview is published on two consecutive pages to provide an unabridged version. — Ed.

China remains far inferior to the U.S. in terms of aggregate military power, but it would be wrong to underestimate China’s abilities to challenge the U.S., particularly in areas close to the Asian power, U.S.-China expert Eric Heginbotham said.

“Geography and distance” factors would come into play to offset many U.S. military strengths should a conflict between the two powers occur in areas near China, said the principal research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for International Studies.

“The PLA (People’s Liberation Army) does not have to catch up with that of the U.S. in overall capabilities to challenge it in East Asia,” the leading scholar told The Korea Herald.

|

| Dr. Eric Heginbotham |

The following is an unabridged transcript of the interview with Heginbotham.

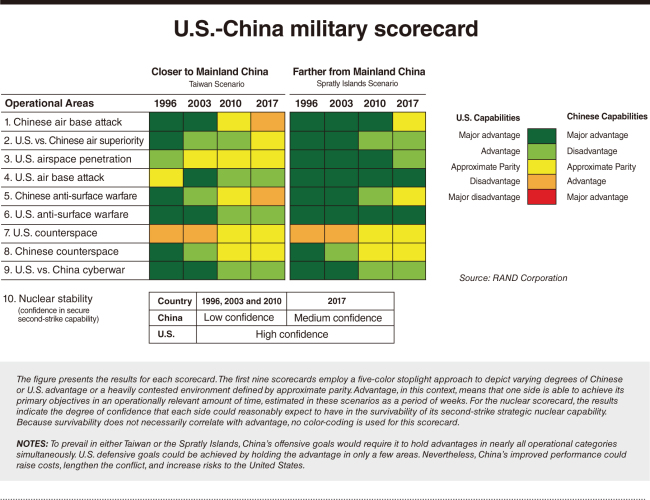

The Korea Herald: You were the lead author of a recent RAND Corporation study “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power.” What was your motivation and how did you organize it?

While much has been written on Chinese military modernization, there has been relatively little structured analysis. Most of the analysis published to date consists of “bean counts,” comparing system numbers, or reports on individual new Chinese weapons systems.

The Scorecards report was an effort to bring structure to the analysis of Asian military issues and fill the current gap in the literature. We sought to capture the most important dynamics that might be associated with combat between U.S. and Chinese forces in particular operational contexts – considering the relevant movement speeds, geography, numbers, quality, and attrition of U.S. and Chinese forces.

The team employed a variety of models and metrics to evaluate the balance in ten different types of operational conflict, at four evenly spaced points in time from 1996 to 2017, and at two different distances from China.

KH: China has been trying to modernize its military for the last several decades. What have been the focal points of China’s military modernization?

Heginbotham: China’s military modernization has been systematic, thorough and broad-based. It began the modernization process shortly after embarking on reform and opening more than 30 years ago, and accelerated its efforts after the Taiwan Straits crises of 1995-96.

After 1996, the Chinese military was focused primarily on forces and capabilities that would be most useful in Taiwan-related contingencies. Its main effort was on strengthening its air and naval forces. It paid particular attention to the development of capabilities that would complicate U.S. intervention in Asian conflicts. Submarines, conventionally armed ballistic missiles and counter-space capabilities were important priorities.

Given Beijing’s focus on Taiwan and the proximity of that island to the mainland, China acquired only modest capabilities to project power to more distant locations. In recent years, however, Chinese leaders have emphasized the need to protect the nation’s overseas interests.

Since 2008, the PLA has maintained a maritime presence in the Gulf of Aden to combat piracy, and it has moved to acquire modest power projection capabilities. The Chinese military has begun series production of destroyers and launched its first aircraft carrier. It has improved its maritime resupply capability and developed prototypes for aerial refueling tankers.

KH: How much has China caught up with the U.S. in terms of military strength so far?

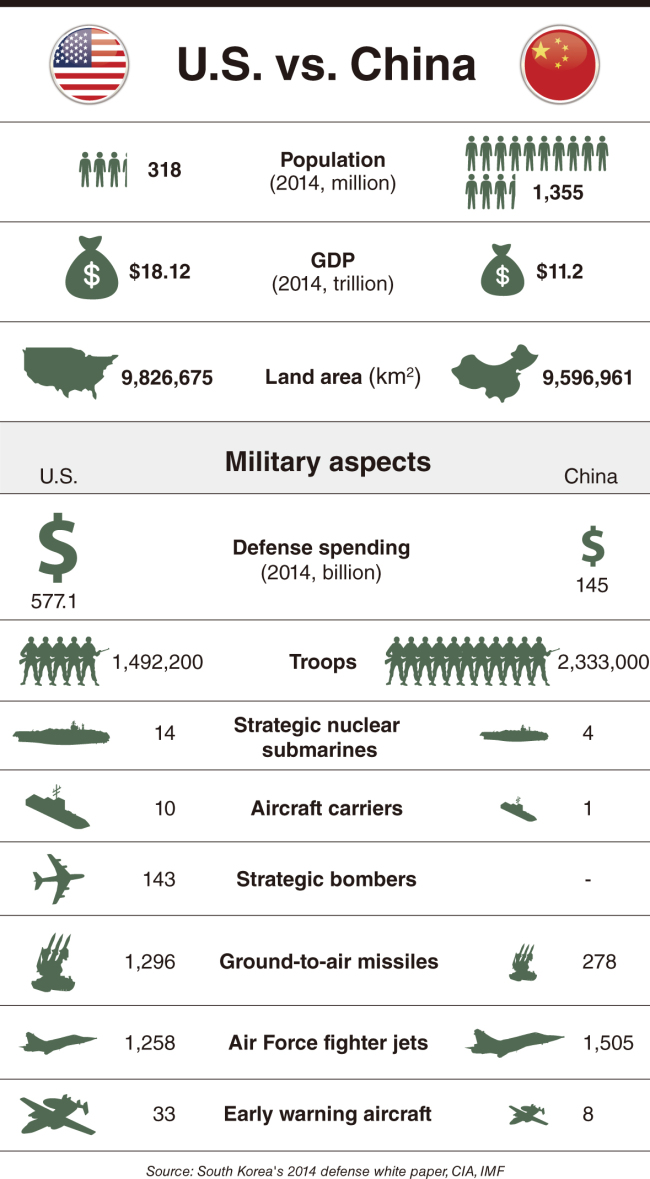

Heginbotham: China had narrowed the gap with the United States in virtually all areas of potential military competition — but it has not closed the gap. Indeed, aggregate U.S. power remains far superior to that of China.

A couple of examples help illustrate the point. China has recently deployed its first aircraft carrier, while the United States operates 10 full-sized carriers, as well as nine amphibious assault ships capable of supporting fixed-wing aircraft. The U.S. military not only maintains roughly twice as many combat aircraft as China, but it also holds significant qualitative advantages. It has been flying stealth aircraft for more than 30 years, while China is only now testing prototypes.

However, considering aggregate military capabilities can be misleading, and it would be wrong to underrate the degree to which Chinese military power can challenge the United States, especially in areas close to the mainland. The PLA does not have to catch up with the U.S. military in overall capabilities in order to challenge it in East Asia.

Geography and distance are critical military factors and would greatly offset many U.S. military strengths. Chinese forces would operate close to their logistical bases, while U.S. reinforcements and resupply would flow from depots thousands of miles away. PLA commanders could employ relatively secure ground-based communications, while U.S. forces would rely heavily on more vulnerable satellites.

Geographic factors within the theater of operations would also complicate U.S. efforts. The U.S. Air Force has one air base (the Kadena Air Base) within unrefueled fighter range of Taiwan, while China has several dozen. To be sure, the United States could use aerial refueling to bring additional aircraft from more distant bases in Japan or elsewhere in Asia, but China could deploy far more aircraft to a fight during the opening stages of a conflict than could the United States.

Moreover, China has developed specific capabilities that would compound the challenges posed to U.S. operations by distance and geography.

KH: What are the strong points of the Chinese military that could threaten the U.S. military?

Heginbotham: As your question implies, it is important to consider strengths and weaknesses in the context of a larger “system of systems,” as well as in the context of specific operational circumstances.

A historical example may illustrate the point. U.S. tanks during World War II were inferior to German ones, but U.S. airpower and artillery, as well as general material preponderance more than compensated for the weakness in U.S. armor, which tried to avoid taking on German tanks in head-to-head duels.

China has achieved some interesting and significant technological breakthroughs, such as the modification of ballistic missiles to attack moving ships at sea — a first not just for China, but also for anyone. More importantly, China has developed an array of systems and capabilities that compound the challenges to U.S. forces associated with geography and distance.

For example, the PLA has deployed more than 1,300 ballistic missiles, many extremely accurate, as well as hundreds of long-range cruise missiles. These systems could attack and damage or disrupt U.S. air bases and other critical infrastructure. Given America’s long lines of communications and the relative paucity of basing available to it in Asia, missile attacks on U.S. facilities could severely limit the ability of U.S. forces to flow reinforcements into the theater and operate effectively once there.

In addition to the threat to U.S. air bases, the PLA’s ability to hold U.S. aircraft carriers at risk further compounds the challenge to U.S. airpower. In addition to the antiship ballistic missiles I mentioned earlier, China operates roughly 40 modern attack submarines. Although these submarines are not as advanced as U.S. designs, submarines are not primarily designed to fight other submarines. China’s newer submarines are armed with cruise missiles and could be deployed to lie in wait for U.S. carriers operating in the South China Sea or Western Pacific.

The PLA has recently deployed long-range cruise missiles that fly, during their later stages of flight, at supersonic speeds and would, therefore, be extremely difficult to defeat. Depending on circumstances, Chinese surface ships or (more likely) bombers or strike aircraft armed with cruise missiles might also be able to engage U.S. carriers.

U.S. military operations over the last several decades have relied heavily on the employment of airpower operating from secure bases beyond the reach of adversary attack. China’s ability to target and disrupt U.S. land-based and maritime airpower challenges this American way of war. U.S. aircraft and pilots remain formidable and the PLA air forces would not likely “win” an air war that stretched beyond a single month. But they might nevertheless contest air superiority long enough for other Chinese forces to achieve operational objectives.

KH: What would be the Chinese military’s weak points? How do you think China would try to overcome them?

Heginbotham: As I noted earlier, China has narrowed the gap in military capabilities with the United States, but remain inferior in many respects. Some of these weaknesses would have a particularly significant impact on outcomes if a conflict were fought today.

PLA antisubmarine warfare capabilities remain rudimentary, and U.S. submarines, which are the best in the world, could wreak havoc with Chinese amphibious landing fleets. They would pose a serious threat to Chinese surface combatants and, to a lesser extent, submarines. U.S. submarines also carry a limited number of land-attack cruise missiles and could employ these to strike key ground targets at the outset of hostilities, before the United States could achieve the air superiority necessary to launch such strikes from the air.

As I noted earlier, China’s power projection capabilities also remain underdeveloped. At present, it has only a handful of relatively small tanker aircraft that could refuel aircraft in flight. Given the limited range of most fighter and strike aircraft, the lack of tanker support effectively limits PLA Air Force operations to areas on China’s immediate periphery. The PLA Navy faces similar, if less severe, limitations in its ability to sustain operations at a distance from the mainland. China’s defense industry, for its part, is greatly improved, but still experiences persistent weaknesses in some areas. It has, for example, faced persistent trouble producing the high-performance aircraft engines required for high-end fighter aircraft, and China continues to import a large number of engines from Russia.

The PLA also suffers from deficiencies in training and operational competence. Its heavy emphasis on centralized, top-down planning and command limits flexibility and initiative at the unit level. Its training system lacks many of the institutional structures that support realistic training in the U.S. military. Compounding this problem is the lack of Chinese combat experience since its border conflict with Vietnam, which began in 1979 and festered through the early 1980s.

One of the great strengths of PLA modernization has been the leadership’s ability to identify deficiencies and adopt sustainable, incremental measures to address them. In this point there are few glaring deficiencies, and the PLA is addressing virtually all of them. It has, for example, rolled out three new purpose-built antisubmarine warfare platforms since 2012, including a fixed maritime patrol aircraft, a helicopter and a corvette. China’s weapons systems will not match U.S. numbers nor quality in many cases, but the PLA will, at a minimum, have at least modest capability in virtually all types of combat — and it will have superior systems in some.

Adequately addressing persistent weaknesses in the areas of training and operational competence will likely take longer than fixing material deficiencies. Organization culture can be slower to change than plugging material gaps. Nevertheless, many Chinese military leaders appear to understand the need for greater flexibility in modern warfare, and China is steady, if slow, in fostering a more dynamic force.

KH: Can you talk about China’s defense spending? Is it a formidable amount or increase over the last decades? If so, why is it formidable?

Heginbotham: Between 1996 and 2015, China’s official defense spending, adjusted for inflation, increased by roughly 650 percent – or an average of more than ten percent per year. This sustained increase in defense spending and advances in Chinese technological and industrial strength are the primary material factors underlying the rapid modernization of Chinese military forces.

Growth in defense spending has tracked fairly closely with the expansion of the Chinese economy as a whole, and even more closely with the increase in overall government spending. It is perhaps natural that leaders of a rapidly growing economy will look to have commensurate military capabilities. Japan’s defense budget grew rapidly during its bubble years, as has South Korea’s more recently. China’s defense spending as a percentage of GDP is not particularly high, and I would be hesitant to infer too much about Chinese intentions from growth in its military budget alone, given the growth of China’s economy as a whole.

That said, it is also clear that the combination of growing Chinese military power and a growing willingness to assert its prerogatives forcefully has prompted great unease throughout the region. Unless Beijing moderates its behavior, Chinese international behavior has the potential trigger regional balancing and arms racing that could not only undermine regional stability, but also endanger China’s own long-term strategic interests. China will need to do more, rather than less, to reassure neighbors as its power grows, but its behavior indicates that it may instead look to achieve longstanding objectives at the expense of others.

KH: Many say China’s announcement of defense budgets is not transparent. What is your take on this?

Heginbotham: China’s reporting on defense spending clearly lags behind that of most advanced democratic states in terms of transparency. Most Western analysts suspect that Chinese reporting understates actual military-related spending. While this is true, it should be noted that few if any defense budgets – even in the West – fully reflect defense-related expenditures. In the United States, for example, budgets for veterans’ affairs, intelligence, and some military-related nuclear programs are not included in the defense budget, though data on them may be found in other parts of the federal budget.

Some elements of Chinese defense-related expenditures, such as spending on paramilitary forces, can be found in other parts of China’s published budget. Other components, such as subsidies for defense-related research, can only be estimated based on larger categories of expenditures on science and technology. Greater transparency would not only give outside observers a better sense of China’s priorities – and the rationale for modernization – but they would also reassure the outside world that Chinese civilian leaders and analysts have an understanding PLA direction, a necessary though not sufficient condition for exercising effective oversight.

Heginbotham: China has been making steady and relatively rapid relative gains vis-a-vis the United States. These gains are not uniform across the different military domains, and the United States has maintained its lead more comfortably and decisively in some areas than others. But the erosion of U.S. dominance has nevertheless been widespread and significant.

In terms of aggregate capabilities, China will not be able to overtake the United States for decades, if it ever reaches such a point. If a military conflict were to take place at an equal distance from both countries, the United States would hold overwhelming advantages for the foreseeable future. But China has already acquired capabilities that would enable it to challenge the United States in areas close to China, and the risks and costs associated with potential conflicts in East Asia will likely continue to grow for U.S. forces in the years ahead.

Given Taiwan’s proximity to China, as well as its small size and lack of strategic depth, Taiwan-related contingencies would be among the most difficult for U.S. forces. In a hypothetical Taiwan scenario, the PLA would likely be able to contest air and maritime superiority at the outset of the conflict, and it might inflict losses on the United States unlike any the latter has seen in recent decades. The Chinese military could employ ballistic and cruise missiles to damage U.S. air bases and other critical facilities; it could flush submarines and sortie cruise-missile-armed bombers to hold U.S. carriers at bay; and it could employ combat aircraft — which now includes roughly 800 fourth-generation, or modern, fighter aircraft — to contest air superiority and launch follow-up strikes against key targets.

To be clear, U.S. forces would almost certainly prevail in a Taiwan scenario today — especially if a conflict became protracted. The U.S. military has tremendous residual strengths and could redeploy forces from elsewhere to make good initial losses.

Amphibious landing operations are notoriously complex and hazardous, and in any Chinese attempt to take the island by force, its amphibious fleet would face ferocious and unforgiving attacks by U.S. submarine and air forces. Blockading Taiwan might be somewhat easier, but a blockade would, by definition, require sustained operations, and the PLA would have great difficulties supporting such efforts.

Conflicts at greater distances from China would generally be even more difficult for China, given its limited power projection capabilities. In those cases, U.S. forces could operate from bases outside the range of most Chinese ballistic missiles, and far fewer Chinese aircraft could get themselves into the fight.

Nevertheless, if Chinese capabilities continue to improve at their current rate and the United States does not make significant adjustments to its operational practices and procurement, the defense of Taiwan will likely become far less certain within 10-15 years. China will also likely improve its ability to project power beyond Taiwan, though the scale will remain more limited and the United States will enjoy clearer advantages as the distance from China increases.

KH: How do you assess China’s overall capabilities to project military power to the South China Sea and conduct military operations there? Would it be possible for China to risk any intense military clash there?

Heginbotham: The Chinese military’s ability to project power toward the Spratly Islands remains limited. The Spratly Islands lie roughly 900-1,400 kilometers from China’s Hainan Island — significantly farther than Taiwan, which is a mere 160 kilometers off the mainland. Without aerial refueling, Chinese fighter aircraft would be operating close to the limit of their range, with little fuel to spare for combat operations once there. Amphibious forces would similarly have to traverse long distances, increasing their exposure to air and submarine attacks.

Against relatively weak local competitors, Chinese forces deployed to the South China Sea might prove adequate for a variety of tasks, but they would likely face enormous disadvantages against U.S. opposition.

In recent months, China has undertaken large-scale land reclamation in the South China Sea and is constructing large (3,000-meter) airstrips on at least three of its new islands. The islands and the military facilities on them will enhance China’s ability to maintain an air presence during peacetime, and they will provide it with additional capabilities against potential local adversaries in the event of conflict. But Chinese facilities on the Spratly Islands would likely be highly vulnerable to attack during a conflict with U.S. forces. The mobility of modern surface-to-air missiles would be of little value on the tiny new artificial islands, and there would be few opportunities for air defense in depth, involving interlocking range rings and missile types.

China’s land reclamation in the South China Sea, with its potential impact on territorial claims, has garnered considerable media attention, but from a strictly military perspective, improvements to the PLA’s underlying sustainment capabilities will likely be at least as important — perhaps significantly more so. China will soon deploy its first indigenously built military transport aircraft, the Y-20, and the PLA is likely to build a tanker variant. A significant fleet of tankers that are each larger than the handful it now deploys would enable China to fly more aircraft, with greater loiter time, from more bases to areas throughout the South China Sea — as well as into the Western Pacific.

As far as the likelihood of conflict, China’s political leaders have every reason to avoid conflict with regional states, and even more to avoid an armed clash with the United States. However, it is possible to imagine situations in which a local incident or crisis could escalate to the use of force, especially if Chinese leaders believed that the United States would remain on the sidelines. In the context of an ongoing crisis, it might prove impossible for either China or a potential adversary to back down in the face of aroused public opinion. And the United States, with its credibility on the line, could potentially be drawn in for reasons other than its direct interests in the dispute in question.

Accidents and miscalculations are, in my view, the most likely paths to conflict between China and the United States. And with Chinese military power growing, PLA military aircraft and ships now come into contact with those of its neighbors and the United States more frequently, increasing the risk of accidental or incidental crises or clashes.

KH: How do you assess China’s nuclear force? Some people say when China secures an adequate level of conventional military capabilities, there could be a move to strengthen its nuclear force.

Heginbotham: Chinese leaders and strategists have long believed that nuclear forces are critically important for deterring nuclear attack and blackmail, but they have also held that, beyond deterrence, nuclear weapons’ functions are very limited. China maintains a no-first-use policy, and many Western analysts describe its doctrine as one of “minimum deterrence.” Western and Chinese analysts note that Beijing has not accorded the development of a large and robust nuclear force the same priority that it has to the modernization of conventional forces.

Nevertheless, the pace of Chinese nuclear modernization has accelerated in recent years. The PLA has deployed more weapons and improved the quality and survivability of its new systems. In large measure, nuclear modernization appears to have been driven by concerns about the ability of Chinese nuclear forces to survive a hypothetical U.S. first strike in sufficient numbers to penetrate U.S. missile defenses and retaliate. Therefore, the emphasis has been on the deployment of new classes of mobile land-based missiles, as well as improved ballistic missile submarines — all designed to enhance survivability.

China will probably not abandon core policies or elements of strategic thought, but it will continue to improve its nuclear capabilities. Those improvements may give it new options with regard to nuclear warfighting and could lead it, in the longer term, to reinterpret doctrine even as it continues to cling to the same lexicon and labels (for example “no first use”).

While nuclear deterrence vis-a-vis the United States will continue to be the focus of China’s nuclear efforts, Chinese strategists are also likely to pay increasing attention to the development of nuclear capabilities in neighboring states, particularly in India and Russia. Although the number of nuclear weapons deployed globally continues to shrink with the reduction of U.S. and Russian inventories, nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence is likely to gain increased salience in Asia, where Chinese, Indian, Pakistani and North Korean capabilities are all growing.

KH: What are the implications of Chinese military modernization and the evolving balance of power for Korea?

Heginbotham: The shift in the balance of power over several decades has indeed been profound. In 1996, China’s defense budget was less than half the size of that of Japan, which at that time was the largest in Asia. Today, China’s budget is three times that of Japan’s, and improvements to its capabilities have been commensurate. Needless to say, Chinese military budgets and power compare even more favorably with those of other Asian states, including Korea’s, despite major improvements to ROK (Republic of Korea) capabilities in recent years.

The Chinese leadership’s confidence in the state’s ability to achieve its regional objectives has grown in tandem with the growth in its military power. Chinese objectives and claims have not necessarily become more expansive, but Beijing’s willingness to assert its position forcefully certainly appears to have increased. Whether or not it is behaving “aggressively,” or simply more “assertively,” concern has risen throughout much of Southeast Asia. Even Malaysia, with an ostensibly “special relationship” with China, has grown increasingly wary of China’s direction.

In Northeast Asia, Korea has cultivated its own special relationship with China, chiefly to better handle its relationship with North Korea. China’s disputes with the ROK are relatively minor and have thus far remained largely submerged. But as Chinese power grows and its behavior alters in tone if not totality, there is no guarantee that Beijing’s activities in Northeast Asia will not evolve in ways that will present new challenges to Seoul. The U.S.-ROK alliance will likely become more important to both partners in the years ahead as uncertainty mounts.

KH: How do you think the U.S. military will try to maintain its military leadership amid the rise of the Chinese military?

Heginbotham: Barring dramatic changes in U.S. or Chinese economic fortunes, it may be impossible for the United States to maintain the kind of military dominance that it once held. Nevertheless, the United States can maintain a powerful conventional deterrent — and more broadly, an important security role — in Asia.

Doing this will likely require the adoption of an integrated set of military and political measures. To some extent, the U.S. military can improve its position by adjusting procurement priorities. The United States has global strategic interests and requirements, and much of its efforts since Sept. 11, 2001, have focused on capabilities associated with counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East. Over the last several years, however, it has begun to place greater emphasis on acquiring or improving capabilities most relevant to the Asia-Pacific, including the acquisition of new types of long-range precision strike and more robust satellite systems that are resistant to, if not immune from, jamming and dazzling.

Even more fundamental than changes to procurement will be adjustments to operational concepts and posture. There is vigorous debate in U.S. security circles about what specific changes should be made to defense strategy in Asia. In my view, the United States should adopt an active denial strategy that focuses on maintaining resiliency in the face of attack and on the ability to defeat adversary forces actively engaged in offensive operations. Survivability would derive in part from the dispersion of U.S. military assets and the repositioning of some farther from the mainland, as well as from the hardening of military facilities and modest improvements of active defenses (such as missile defense systems).

Assuming relatively flat budgets, such adjustments could entail some loss of offensive punch at the outset of conflict and would implicitly acknowledge that all-aspects military dominance is beyond U.S. reach. But they would also highlight continuing U.S. commitment to the region and would, in the end, strengthen deterrence. One of the few areas of consensus to emerge from the large literature on deterrence theory is that potential aggressors are more likely to attack when they have a plausible path to quick success. Any increase in U.S. operational resilience — the ability to absorb punishment and continue the fight — should therefore have a powerful deterrent impact.

And because the strategy would be both less “forward leaning” (offensively oriented) and more survivable, an active denial strategy would reduce the incentives for both sides to strike first in the event of crisis. In other words, it would enhance, rather than undermine, crisis stability.

In addition to changes to procurement and operational concepts, it will be critical for the United States to deepen strategic relations with regional allies and leverage the strengths of those partner states. Indeed, without allied support and cooperation, it will be impossible to achieve the military objectives outlined above or to pursue alternative operational concepts. More broadly, a united front among regional states will maximize the chances that freedom of navigation and other core international norms will be maintained and upheld, and that potential aggression will be deterred.

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

**Eric Heginbotham

● Heginbotham, a principal research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for International Studies, is well known for his extensive research and expertise in East Asian security issues. Prior to joining MIT last month, he was a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

● He previously worked as a senior fellow of Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and taught as a visiting faculty member of Boston College’s Political Science Department. He served for 16 years in the U.S. Army Reserves and National Guard.

● He has authored or coauthored a series of influential books such as “The U.S.-China Scorecard: Forces, Geography and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996-2017” (2015) and “Chinese and Indian Strategic Behavior: Growing Power and Alarm” (2012).

● His articles on Japanese and Chinese foreign policy, and strategic issues have appeared in Foreign Affairs, International Security, Washington Quarterly, Current History and The National Interest.

● Heginbotham received his B.A. from Swarthmore College and his Ph.D. in political science from MIT. He is fluent in Japanese and Chinese.