“We may not have money, but we have our pride.”

This year’s smashing box-office hit “Veteran” — a cathartic action thriller following a detective trying to arrest a sociopathic young chaebol scion on criminal charges — offered arguably one of the most positive portrayals of Korean cops. The detective Do-cheol (played by Hwang Jeong-min), as reflected in the above famous quote, is fierce, righteous, capable and, most of all, ethical. He does not exchange his dignity for his own safety, comfort or more money.

Among many jobs in the world, some require more social responsibility than others. Theoretically, all police officers should strive to be like Do-cheol. But the portrayal of cops in Korean cinema hasn’t always been favorable, reflecting the nation’s modern history heavily influenced by military authoritarianism and frequent abuse of governmental authority. In many significant cinematic works, Korean cops are often linked with corruption, injustice, incompetence and even violation of human rights.

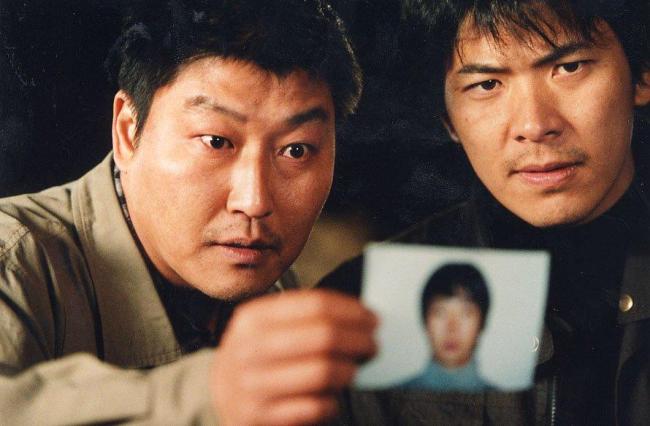

|

| A scene from “Memories of Murder” (Cydus) |

In the 2012 film “National Security,” which recounts torture suffered by late democracy activist Kim Geun-tae, one of its police officers is dubbed the “torture expert.” The character (played by Lee Gyung-young) was based on real-life police officer Lee Geun-an, who is notorious for torturing student activists during Chun Doo-hwan’s military regime in the 1980s. With Lee’s performance, the film successfully serves its obvious purpose — to let its viewers witness the horrors experienced by democracy activists under Chun’s regime.

The cop character is portrayed as ruthless and sadistic to victims, while being extremely loyal and obedient to his superiors. Starting with waterboarding, Lee administers electric shocks and forces Kim to swallow chili powder with water, while making sure Kim does not get any external scars and does not die.

Then, in 2013 film “The Attorney,” viewers witnessed police officers who were similar to Lee in “National Security.” The film is inspired by late President Roh Moo-hyun’s earlier years as a lawyer in Busan. In it, the protagonist (based on Roh), who is enjoying a comfortable life as a tax lawyer, decides to devote himself to human rights after witnessing a university student brutally tortured by the police who accuse him of being a North Korean sympathizer.

The officer who tortured the student shamelessly testifies in court that he followed the state’s order to torture the student, which enrages the protagonist. In the particular scene, the attorney famously shouts back at the officer, reciting Article 1 of the Korean Constitution: The sovereignty of the Republic of Korea shall reside in the people, and all state authority shall emanate from the people.

|

| A scene from “New World” (NEW) |

“Films don’t portray reality, but they certainly reflect how people view reality,” columnist Jeong Deok-hyeon wrote last year. “In ‘The Attorney,’ it is the government that destroys the young university student. It’s the government’s arrogance that even ignores its constitution.

“In the 2008 crime thriller ‘The Chaser,’” he continued, “it is police incompetence that lets the serial killer run away and murder more victims. These films show how the Korean public perceives the public authority. The government is not trustworthy and therefore we have to protect ourselves.”

In the 2000s, detective characters in films were more likeable — although “old-fashioned.”

Film critics Lee Jong-do and Kim Hyeon-jeong wrote in their 2005 piece that most of cop movies at the time — “Memories of Murder” (2003), “Nowhere to Hide” (1999) — feature detective characters who are “old fashioned” but “somehow favored by the viewers” — “they curse all the time, seek fortune-tellers for advice, and feel there is nothing wrong with torturing their suspects” — while introducing white-collar criminals, such as fund managers or former gangsters who illicitly established a successful business (“Public Enemy” (2002), “Beast” (2006)).

“Korean films (in the 2000s) made old-fashioned and likable cops chase white-collar criminals who benefited from the neoliberal economy,” the critics wrote in the piece. “This reflects the collective feelings of loss among Koreans, after undergoing the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s including massive layoffs.”

In the 2010s, Korea has arguably been welcoming more diverse police films. The 2013 film “Cold Eyes,” for example, featured detectives from the surveillance team of a special crime unit who work together to take down a bank-robbing organization. Another 2013 film, “New World,” featured a detective who is assigned by his selfish, manipulative boss to spy on one of the biggest crime organizations in the country.

The detective’s undercover investigation goes on for eight years, and he eventually finds himself caught between the gang’s second-in-command who genuinely trusts and cares for him and his senior detective who only uses him while refusing to protect him when he is in need or in danger. The film blurred the boundaries between good and bad, legal and illegal — and offered the question that many Koreans today are faced with in the aftermath of the 2014 Sewol disaster, a ferry that sank and killed 304 on board: What do we do when those who are supposed to protect us — such as the public authority — betray us?

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)