Uncertainties loom over whether the nation’s death with dignity bill will be passed before the current parliamentary term ends after the general elections in April.

South Korea’s parliamentary committee on Thursday delayed its approval of the so-called “well-dying” bill — which allows patients with incurable diseases to end their own lives by rejecting any life-sustaining treatment. The biggest stumbling block is the ongoing debate among lawmakers on whether or not traditional Korean doctors should also be allowed to participate in treatment at hospices.

All pending bills are automatically discarded after parliamentary term ends, so it remains unclear whether the bill will be passed at all.

|

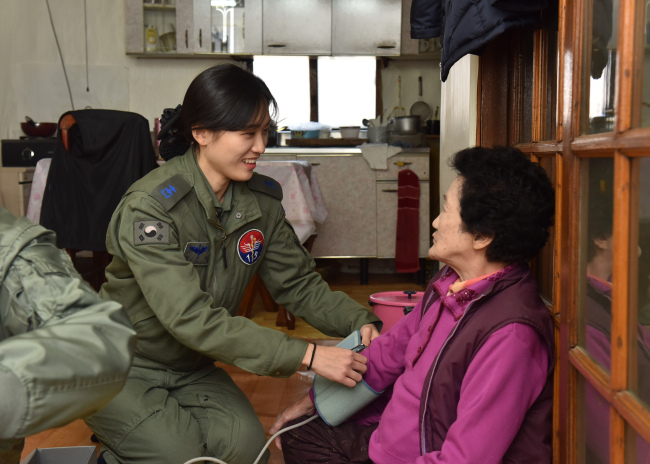

| An elderly Korean woman (right) is receiving medical care from a military nurse. Yonhap |

Prior to the session of the parliament’s legislation and judiciary committee’s session last Thursday, the bill had been passed by a parliamentary subcommittee Tuesday. The final approval was delayed, as some lawmakers, including Rep. Kim Jin-tae of the ruling Saenuri Party, suggested the bill should acknowledge traditional Korean treatments, such as acupuncture, as treatments that can be life-sustaining or manage pain.

The lawmakers also suggested Korean traditional doctors should be given the authority to declare a cancer patient’s condition incurable, giving him or her the option to discontinue treatment and opt for pain management instead.

The bill currently defines life-sustaining treatments as chemotherapy, mechanical ventilation, blood dialysis and CPR and other treatments approved by a presidential decree. It does not specifically acknowledge any traditional Korean treatments as serving to prolong life without reversing the underlying medical condition.

A number of media reports claimed that Rep. Kim and traditional medical doctors were being unreasonable, saying very few traditional treatments can serve as a life-sustaining care option for fatally ill patients.

The Association of Korean Medicine, one of the biggest representative groups of doctors of traditional Korean medicine, said they are unfairly blamed for the delayed approval of the bill, and that their intention was to ensure clarity in the legislation.

“We agree with the intention of this bill and believe that it should be approved and passed at the National Assembly as soon as possible,” said Kim Ji-ho from the association.

“What we wanted was to either clearly limit the legally acknowledged life-sustaining treatment options as the four — chemotherapy, mechanical ventilation, blood dialysis and CPR — by removing the clause ‘other treatments approved by a presidential decree,’ or specifically include more treatment options, including traditional medicine care, in its definition of life-sustaining treatment.”

In addition, Kim claimed traditional herbal medicine could help cancer patients with pain management, as well as with fatigue during chemotherapy.

The Association of Korean Medicine has had a rather turbulent relationship with the Korean Medical Association, the largest body of Korean physicians. The two organizations have been disputed a variety of matters, including the controversial use of nontraditional medical scanning equipment, such as ultrasound or X-ray machines, by traditional medical professionals.

Meanwhile, a survey by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs showed last year that most elderly Koreans did not wish to receive life-sustaining treatments if they had a grievous and irremediable medical condition. According to the research, 88.9 percent of all Koreans aged 65 or older as of last year did not wish to receive such treatments if they knew their medical condition could never be cured.

Many countries, such as Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and a number of U.S. states including Washington, New Mexico and Oregon, allow physician-assisted dying. Although Korea’s “well-dying” bill does not legalize physician-assisted dying — it only allows rejecting any life-sustaining treatment and surrogate decisions by family members if the patient is incompetent or unconscious — it would’ve been the nation’s first “death with dignity” regulation if it were passed by the National Assembly on Thursday, allowing it to come into effect from 2018.

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)