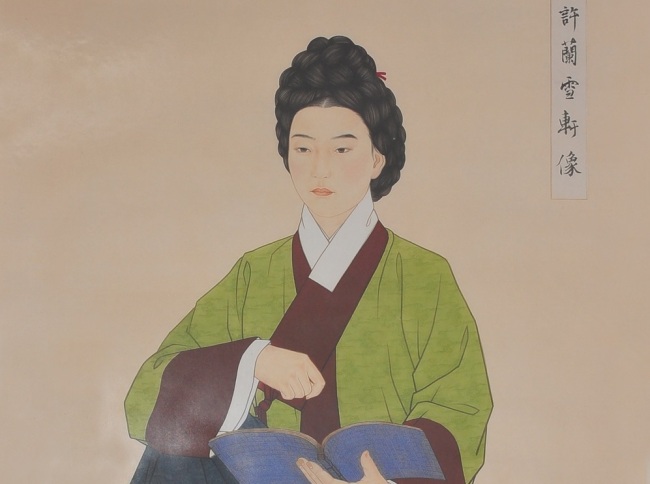

When Heo Nanseolheon (1563-1589) was just 8 years old, she wrote her iconic piece “Inscriptions on the Ridge Pole of the White Jade Pavilion in Kwanghan Palace,” a poem filled with a unique imagination about the world of spiritual beings. Today, the piece is still considered as the work of a poetic genius — who later died at age of 27, after suffering an unhappy marriage and the deaths of her two children.

Heo is one of very few women writers from Korea’s Confucian Joseon kingdom (1392-1897), where most women were not allowed to learn how to read or write. She is also one of a handful of figures in Korean history who are considered geniuses, many of whom lived tragic and extraordinary lives.

As Oscar Wilde once famously said — “the public is wonderfully tolerant; it forgives everything except genius” — they often suffered misfortune and misunderstanding in spite of — and perhaps because of — their remarkable talents and achievements.

Stories of their lives challenge the modern definition of prodigies in today’s South Korea, a nation known for its hyper-competitive education system and its unhappy and stressed students.

|

| Heo Nanseolheon |

One of the modern-day individuals who have been considered as child prodigies is Song Yoo-geun, whose recent paper submitted to the Astrophysical Journal was retracted over a plagiarism scandal. Back in 2005, he made national headlines by becoming the youngest university student ever, when he was only 8. If his paper had not been retracted, Song would have been the youngest-ever South Korean to earn a Ph.D.

Song’s recent fall was triggered by his own ethical violations, as was the disgraceful scandal of Hwang Woo-suk, who had been considered one of the pioneering experts and geniuses in the field of stem cell research — until it was shockingly revealed in 2005 that many of his experiments featured in high-profile journals had been fabricated.

Yet many misfortunes suffered by Korean geniuses in history were in fact created by something that was beyond their control — including the caste system, gender-based discrimination, and even the Korean War.

“In Heo Nanseolheon’s time, women were invisible. Only their husbands’ names were recorded on the genealogical record,” wrote scholar Heo Kyung-jin, who translated Heo’s poetry from the traditional Chinese to modern Korean, in 2013.

“But Heo chose to have a name, and chose to be different when it was almost unthinkable to do so. And her choice is what triggered her misfortune, but it’s also proof that she fought throughout her life.”

Heo enjoyed the rare privilege of learning literature as a child, thanks to her brothers who noticed her talent and insisted she receive an education in spite of her being a girl.

Yet her unhappy marriage to a civil official, which also led to isolation from those who supported her talent, slowly brought tragedy to her life. Although she produced some of her most iconic pieces while married, both of her two children died as infants in subsequent years. Not many years later, she suffered a miscarriage. Heo died shortly after her father and elder brother died in exile.

While Heo was a prodigy in Joseon literature, Jang Yeong-sil (1392-1897) was the genius of Joseon’s science and astronomy. He is best known for his inventions, including Korea’s first rain gauge named cheugugi (1441), as well as the world’s first water gauge named supyo (1441), which was created to help farmers with water management.

His achievements earned him much trust of the King Sejong (1397-1450), but it also triggered jealousy among some government officials who looked down upon his nonaristocratic origin.

Also, according to Joseon’s Confucian agrarian bureaucracy, skilled workers and scientists were considered lower than the aristocrats, who were mainly composed of military and scholarly officers. Jang was eventually expelled from the royal palace after a gama, a Korean sedan chair, he made for the king broke while Sejong was traveling in it.

In spite of his extraordinary accomplishments, there is no remaining record of his post-exile life and even the date of his death.

In the 20th century, Korea welcomed two female geniuses in the field of arts. One was Na Hye-seok (1896-1948), the first feminist professional painter and writer in Korean history. Having studied oil painting at Tokyo Arts College, she was also actively engaged in writing and the independence movement against Japan’s colonial rule.

She was also one of the first women in Korea who vocally resisted the feudal patriarchal system, even after it became public that her husband divorced her on grounds of infidelity. In 1934, three years after she divorced her husband, Na published a very controversial piece called “A Divorce Confession,” which fiercely challenged Joseon’s male-oriented marital conventions, and openly criticized her ex-husband.

After her public reputation was ruined post-divorce, Na lived a lonely and destitute life — her ex-husband never allowed her to see their children and left her with no money — until her death in a hospital for vagrant beggars in Seoul in 1948.

“Na Hye-seok’s goal was to go against her time and find something new, rather than to be the ideal figure of her times,” wrote Han Dong-min from Suwon Museum, who organized an exhibition featuring Na’s remaining paintings in 2012.

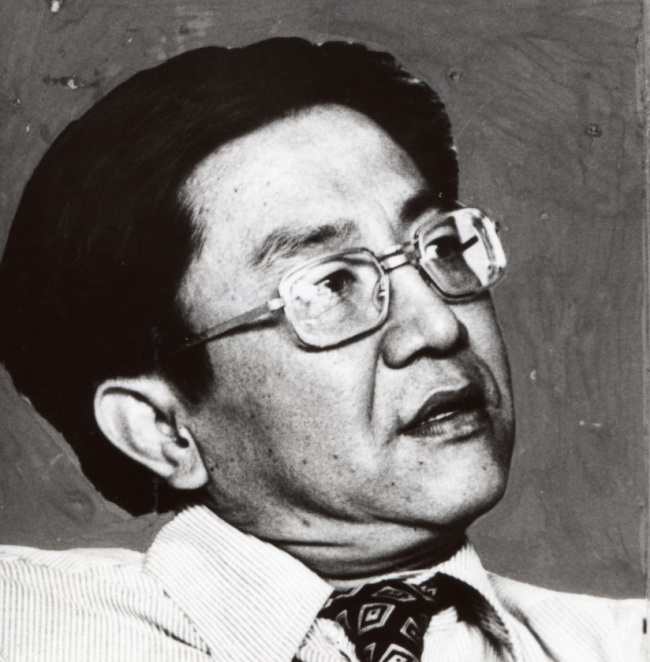

|

| Lee Whi-soh |

“Instead of becoming what was expected of her at the time — a composed, well-behaved, intelligent and educated woman — she stayed true to who she was, as well as her passion and desires. And I think that’s what she thought was needed for women in Joseon. Desires and passion, not knowledge or discipline.”

Choi Seung-hee, lauded as one of the best dancers in Asia in the early 20th century, was born in 1911. Her life was entwined with Korea’s post-colonial politics, the Korean War and national division. Trained under Japanese modern dancer Baku Ishii in Japan, with the support of her wealthy parents, Choi developed her own style which combined Korea’s traditional dance movements and what she learned from Ishii.

Her 1939 performance in Paris was attended by Pablo Picasso, who described Choi as “a real artist who exceptionally portrays the dream and ideal of our time period.”

Yet following Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, Choi was condemned in Seoul for performing for Japanese troops during the Sino-Japanese War, in spite of her reputation as a genius. She eventually defected to today’s North Korea in 1946, and was purged by the North Korean regime in 1967. It was only in 2003 that Pyongyang made an official confirmation of her death in the 1960s.

“Choi Seung-hee was a creative, innovative artist who recreated the forgotten and traditional into something new, with her thorough research. She was the first hallyu star, who already charmed audiences in Japan, China, the U.S., Europe and South America back in the 1930s,” said Kang Joon-shik, whose biography of Choi was published in 2012 on the centennial of her birth.

In 1977, Lee Whi-soh, a Korean-born, America-based theoretical physicist, abruptly died in a car accident at age 42. He is best known for his work in theoretical particle physics, which had a great influence on the development of the standard model in the late 20th century, as well as gauge theory.

On top of his research achievements, he is also known for having been critical of South Korea’s military regimes in the 1960s and 70s. He reportedly canceled a science education project he planned to hold in Seoul to avoid showing support to the authoritarian government in 1972.

In today’s South Korea, what made some of the most successful stories of modern-day geniuses — such as Song Yoo-geun and Hwang Woo-suk — were shockingly revealed to be lies and ethical violations.

A university professor who wanted to remain anonymous said today’s definition of prodigies are deeply linked with Korea’s nationalism as well as economy-driven ideology.

“There is this notion that one genius or hero can feed or save everyone, which can be also seen as it’s more efficient to invest in a single exceptionally talented person than support as many people as possible,” he said, mentioning Hwang’s scandal.

Yet many great minds in history emphasized the importance of truth when mentioning geniuses. In every work of genius, we “recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty,” wrote American essayist R.W. Emerson (1803-82).

“The reason we have so few geniuses is that people do not have faith in what they know to be true,” he also wrote.

And what also resonates in modern-day Korea is a quote by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe.

“The first and last thing required of genius is the love of truth.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)