At a glance, Yiombi Thona appears to be a symbol of success as a refugee in Korea, with his thriving career as a university lecturer and human rights activist traveling around the world to address refugee problems.

Yet, he could settle down in Korea only after a grueling six-year process to win refugee status, enduring poor treatment toward asylum seekers and discrimination against African migrants.

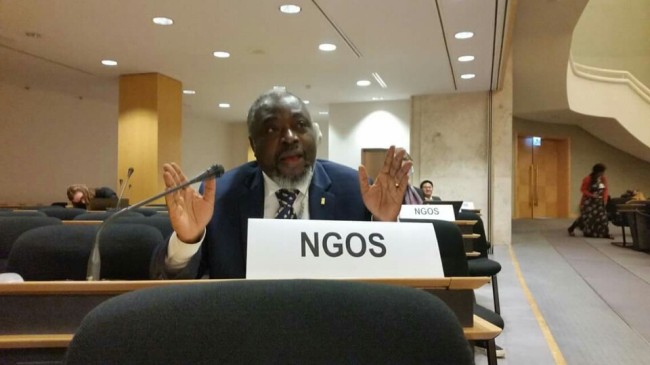

|

| Yiombi Thona |

“Korea is my second home which gave me protection. I appreciate it,” Thona, a Congolese refugee and professor at Gwangju University told The Korea Herald. “But living as a refugee in Korea has been challenging, mainly because Koreans don’t know what a refugee is.”

Thona, who was born to a royal family and served as a national intelligence agent for eight years in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, fled his motherland after being tortured and jailed for blowing the whistle on a dubious deal between the government and the rebel army.

With the help of his colleagues, Thona managed to obtain a fake passport to travel to China. He stayed in Beijing for a week looking for a third country where he could claim asylum, as China was diplomatically too close to Congo. He then secured a visa to enter Korea in 2002.

“I barely knew about Korea. I thought I was going to Pyongyang because, in Congo, we were only familiar with North Korea,” he said. “But it didn’t matter where I was going. I just had to stay away from my country.”

After a two-day ferry journey, Thona arrived in Incheon. He took a taxi and ended up at a hotel near Seoul Station.

“I only had a small bag and very little money. I had nowhere to stay and no one to talk to,” he said, recalling the first day he arrived in Korea. “For the first three days, I didn’t go out, eat or do anything. People walking outside the window seemed very strange.”

A few days later, Thona wrote a letter to the U.S. office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees asking for help. With its help, he applied for asylum and went through 15 interviews only to be rejected.

The Justice Ministry took issue with the lack of documents to prove his identity and his inconsistent testimonies during the interviews, Yiombi said.

“But it is nonsense. I couldn’t bring documents from Congo because I had to escape urgently,” he said. “I could not explain my side enough as I was not provided with interpreters who could speak good French.”

Defying the ministry’s rejection, Thona brought the case to the court without knowing that the legal process would take another three years.

“When I asked the Justice Ministry officials where to live and what to do, they said they didn’t have any programs to support asylum seekers,” he said. “They just told me not to work illegally as they would have to arrest me otherwise.”

Under the Refugee Act that took effect in 2013, the government now provides selected asylum seekers with monthly living expenses and state-run accommodation for the first six months upon their application. After that, they are granted a work permit to get a job while their claims are being processed.

But in 2002, without the Refugee Act in place, refugee applicants were banned from working in the country under the immigration law. Without any financial assistance from the government or the U.N. agency, Thona began to work illegally in factories.

There, the French-speaking African, who spoke neither Korean nor English, had to endure several injuries and appalling conditions.

“My bosses sometimes called me ‘nigger’ and beat me when I was slow in understanding new machines,” he said. “I had never done physical work before. I cried day and night. My body ached all the time.”

One night his arm got stuck in a machine and he started to bleed. While his boss yelled at him without helping him, it was a refugee rights lawyer who took him to a hospital at 2 a.m. But the hospital tied Thona to the bed to prevent him from running away as he did not have money to pay for medical expenses, he said.

“South Korea signed the Geneva Convention to receive refugees. But the country offered neither housing nor food to help us to survive back then,” he said. “I wondered where human rights were in this country. How could a human being live like that?”

South Korea’s first engagement in the international refugee movement dates back to 1992 when it joined the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

|

| Yiombi Thona |

Since the country began to accept refugees in 1994, the Justice Ministry has completed reviews on 7,735 applications and granted refugee status to 522 of them as of 2014. Putting aside thousands of pending applications, its refugee acceptance rate stood at 6.7 percent, far lower than the U.N. average of 38 percent.

Thona was eventually recognized as a refugee in 2008. He was then entitled to work, medical insurance, documents to travel outside Korea and, most importantly, the right to bring his family to Korea.

But even after he won refugee status, his ordeal was far from over, he said.

Even with a legitimate visa to work here, employers were reluctant to hire him as he was a refugee. Whenever Thona attempted to pass through border controls with his travel document issued by the Korean government, he was rejected and then had to wait for hours while immigration officers worked out his refugee status.

“It is good that protection for refugees is written in the law, but measures are not properly being implemented due to lack of awareness of refugees in Korean society,” Thona said. “Banks, hospitals, public servants … they don’t know who a refugee is and the refugee law.”

Thona is also worried about his two stateless children born in Korea. As they grow older, he says, they will need a nation to give them a sense of unity and protection.

“My children don’t have any nationality. They are neither Congolese nor Korean,” he said. In Korea, the Refugee Act does not stipulate the status of refugees’ newborn babies. In Congo, the babies cannot be Congolese unless they are registered with the government within six months after birth.

Now, Thona is trying to raise awareness about refugees in Korea and abroad. He has campaigned for refugee rights, attended conferences to share his experience and published a book titled “My Name is Yiombi.”

“The world should help asylum seekers to better integrate into their society,” Thona said. “Nobody knows who will become a refugee next. It can happen to anyone, anywhere, anytime.”

Between busy schedules, Thona misses his homeland every day. One day, he would love to go back.

“I can go anywhere except for Congo. It is sad,” he said. “I don’t forget my people. When I go back, I want to teach Congolese what I learned about Korea’s rapid economic growth and Koreans’ patriotism.”

“My second home is Korea and I am a transnational guy now,” he said. “But my final destination will always be Congo.”

(laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)