On a chilly Friday night last month, 24-year-old U.S. citizen Megan Stuckey had one of her most hurtful experiences in Korea.

She was denied entry to a bar in Hongdae, Seoul, because she was a foreigner.

|

| Ock Hyun-ju/The Korea Herald |

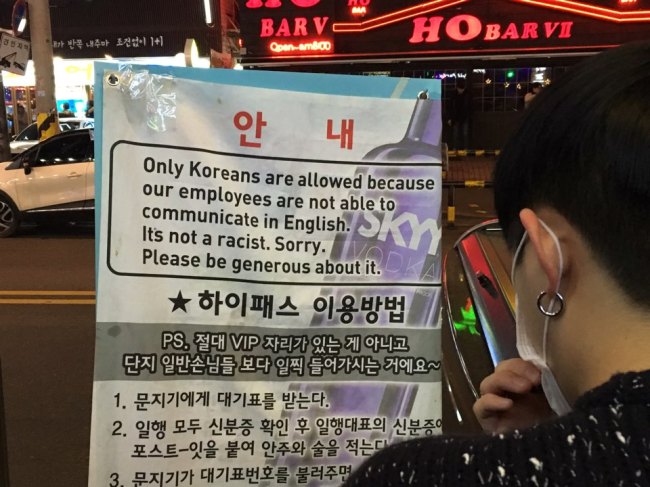

The bar named Green Light, infamous in the expat community for refusing foreign customers, is one of a rising number of Korean-style dating joints where people meet blind dates and one-night stands over beer and soju.

“Only Koreans are allowed because our employees cannot communicate in English,” reads a sign at the door.

“When I asked in Korean, not in English, whether I could get in if I spoke the language, I was still told I wasn’t allowed,” Stuckey told The Korea Herald.

“It’s frustrating as someone who puts the time and effort into learning the language and culture of Korea to be denied entry just because I don’t look Korean,” said Stuckey, who can hold a basic conversation in Korean and teaches English in a public school.

One of the bouncers guarding the door told The Korea Herald that it was not at all their intention to discriminate against foreigners. It was rather their business policy to attract Korean patrons only.

|

| Ock Hyun-ju/The Korea Herald |

“I know that some people think it is racist policy, we really do feel bad,” the 20-something bouncer said.

Another English teacher, 24, from New Zealand, who wanted to remain anonymous, said the “weird” sign would be illegal and offensive back home.

“Korea is vastly developed in technology and economic pursuits but still a little underdeveloped in cultural acceptance and knowledge of the outside world,” he said.

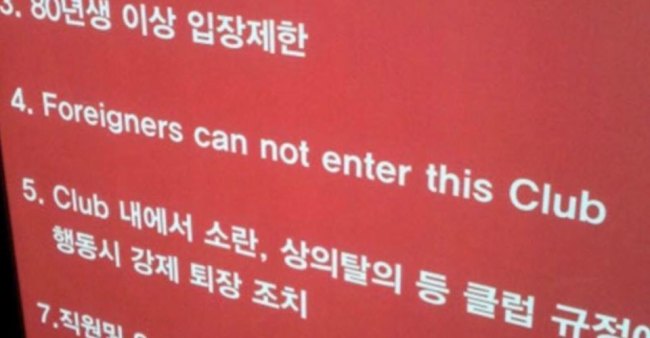

According to several foreign residents The Korea Herald contacted, Korean-only bars are not a general trend, but they exist across the nation, creating perpetual controversy over racism.

AU, the biggest club in Daegu, a city near one of the U.S. Army bases, said it decided to restrict foreign patrons’ entry after several cases of theft and sexual harassment by foreign patrons.

“Once the club starts receiving foreign customers selectively, it could become really complicated,” a manager at the club said. “So we deny entry for all foreigners to the club as a preventive measure.”

A manager of another club in Busan said that it enforced a ban because foreign customers did not respect club rules.

“We refuse foreigners who do not respect the dress code. We also reject Koreans for the same reason. It is just that Koreans understand what we say and do not challenge the policy,” the manager said. “But foreigners who cannot speak Korean fail to get the point, get mad and keep resisting the rule. They just do not listen.”

A 33-year-old American, who lived in Korea for eight years, said that the longer foreigners live here, the more they can understand it is not usually Koreans trying to discriminate.

“Bars and clubs are a social business. They have a certain motivation to go after an atmosphere they want for their business,” he said. “I think when there’s something you want, but you cannot get it, it is much easier to say ‘racism’ than to understand why.”

|

| (Online Community) |

But a 30-year-old woman from the U.S., who was turned down at one of the dating bars around Konkuk University last December, berated the bars for generalizing.

“On any given night of the week, I see Koreans behaving pretty badly as well,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean that the entire race of Koreans should suffer the consequences.”

Korea, a largely homogenous country until the recent rise in number of multicultural families, still lags in catching up to international standards in terms of racism and diversity. There is still no law mandating equal opportunity or preventing people from being discriminated against based on race, religion or sexuality.

The bars and clubs excluding foreign patrons cite freedom of private businesses to decide which customers they serve at their venues.

“I know that a few clubs in Hongdae refuse to accept foreigners, especially American soldiers, based on their past experiences. They have suffered from the U.S. soldiers getting into brawls and creating a ruckus,” said Kim Jung-hyun, head of the Hongdae Tourism and Culture Association. “But it is not a matter of racism. It is up to business owners to determine who to let in.”

|

| (Online Community) |

According to police data, the number of crimes committed by the U.S. soldiers in Hongdae stood at 19 in the first half of last year. In comparison, some 150 crimes were committed by Koreans against foreign visitors in Busan in a 10-day-period earlier this month, according to the district police. They included theft, fraud and assault.

Ordinary Koreans were split over the decision by bars and clubs to keep foreigners out, with some calling it an embarrassment while others blamed it on cultural differences.

“As someone who has seen foreign men getting into fights on the streets, I understand why some bars ban them from entering,” said a Lee Jin-hee, a 22-year-old student, looking for a bar in the clubbing area of Hongdae. “If they spoke Korean, or at least tried to learn Korean culture and manners, they would not be denied.”

But many Koreans like a 29-year-old office worker, surnamed Choi, see such Korean-only policies as shameful.

“I would feel bad if I was refused entry because of my race,” Choi said after seeing a group of foreigners being denied entry to the bar. “Under any circumstances, discrimination should not be allowed.”

Some observers said such a policy may reflect intentional racism, but could also be simply out of ignorance.

“Koreans are often not aware of what can amount to racial discrimination,” an official from National Human Rights Commission of Korea said.

The state-run watchdog has received a few complaints about discriminatory practices in the nightlife scene and opened investigations into the cases.

“Banning foreigners from a bar because of negative perceptions is not a reasonable reason for discrimination,” the NHRC official said. “Such discrimination could be considered a human rights violation and racism.”

|

| (Online Community) |

In 2014, a pub in Itaewon, a multicultural district frequented by foreigners, caused controversy after posting handwritten signs that read, “We apologize but due to the Ebola virus, we are not accepting Africans at the moment.”

The signs went viral on Twitter and Facebook, drawing fury from the expat community.

“Racial diversity is a relatively new concept in Korea and therefore xenophobia is not effectively punished,” the official said. “But when the businesses owners learn it could be seen as discrimination, they quickly correct themselves.”

Bills such as an antidiscrimination law aimed at rooting out bigotry on such grounds as gender, disability, age, race, marital status and religion have been submitted to the National Assembly since 2007 to uphold the Korean Constitution’s value of equality. But they remain deadlocked in the face of Protestant groups’ fierce resistance to equal rights for sexual minorities.

“Without an antidiscrimination act, the human rights commission only has restricted power to fix discriminatory practices based on race,” he said. “The enactment of the law could raise people’s awareness of racism.”

As of December 2015, 1.47 million foreign nationals reside in Korea, about 2.9 percent of the entire population of 51 million.

“Koreans get enraged about bars and clubs abroad discriminating against Asians. Somewhere else, we are also foreigners and outsiders. Everyone in Korea, whether poor or rich, Asian or white, is subject to freedom of choice,” said Yang Eun-sun, public engagement manager at the Korea office of Amnesty International.

“But we should be careful with the enactment of the antidiscrimination law because its loopholes could end up offering grounds for ‘legal’ discrimination.”

By Ock Hyun-ju (laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)