With the Park Geun-hye government refocusing its North Korea policy toward sanctions and pressure, the Unification Ministry faces a formidable task of overhauling the existing cross-border projects and upholding its core raison d’etre: dialogue and cooperation.

Following Pyongyang’s Feb. 7 long-range missile launch preceded by its fourth nuclear test, Seoul set a change in the unruly neighbor’s behavior as its new cross-border policy goal. It announced the effective shutdown of a joint industrial park in the North, funneled nearly every drop of its diplomatic energy into crafting the most crippling U.N. resolution possible and slapped a fresh set of standalone sanctions directed at the regime’s financial and shipping networks.

Then Park crushed a taboo during a parliamentary address on Feb. 16, warning that the communist state would face a “regime collapse” unless it changes course and forgoes nuclear weapons.

|

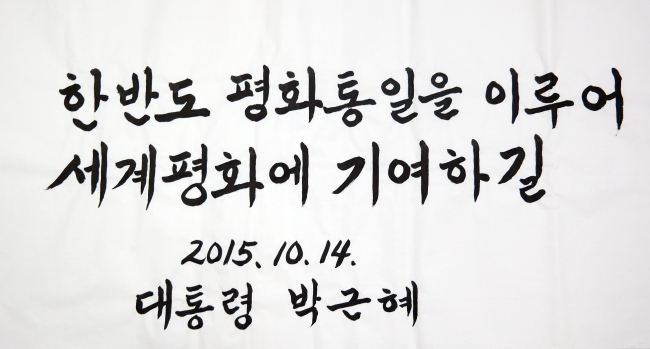

| The image of President Park Geun-hye‘s writing awarded last February to the Unification Ministry. It reads “Achieve a peaceful unification on the Korean Peninsula and contribute to world peace.” (Unification Ministry) |

Amid the sweeping turnaround in the administration’s approach to cross-border ties, the Unification Ministry’s main cause is seen inevitably fading.

Minister Hong Yong-pyo, who would be typically expected to play a dove, has instead been spearheading the hard-line posture, making the case for the Gaeseong industrial park pullout with controversial funds diversion claims. In a speech Wednesday, he once again stressed the need for further pressure as the chief driver of a potential shift in the North, though he did not rule out the possibility of talks.

As tensions continue to flare and virtually all inter-Korean programs are frozen, a downbeat atmosphere prevails across the some 500-strong agency. A self-mocking joke — or tongue-in-cheek rumor — has been circulating throughout the government and media circles, rehashing the 2008 idea that the ministry may soon be absorbed into the Foreign Ministry.

Unification Ministry officials, many of whom are seasoned negotiators and North Korea experts, are striving to do their share. Among the new yet most unlikely responsibilities is a task force on nuclear and peace treaty issues, launched early February.

“While the existing slumps in mood are inevitable, we could carry out things that we had been unable to do when we’re so engrossed in exchange, cooperative projects, such as unification preparation,” a senior ministry official said, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

“The TF team will look into how we can contribute to resolving the nuclear issue within the bilateral framework given that the issue will be on the agenda for any future inter-Korean talks, apart from the Foreign Ministry’s Office of Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs in charge of the six-party denuclearization talks.”

Another ministry official said: “Despite the current strains, however severe they may be, the cross-border relationship may recover in a flash, provided that the sides have the willingness, especially at the top levels. Today’s letup may provide a chance for us to reorganize the internal structure and prop up other pillars including unification education.”

The ministry’s role has constantly been subject to controversy since the then-Board of National Unification was incepted in 1969.

Its heyday came under liberal presidents Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) and Roh Moo-hyun (2003-08). Kim upgraded the agency to a central state organ following his inauguration, and both appointed some of their closest, most powerful aides to steer the budding ministry.

Then it hit the first major snag as former hard-line President Lee Myung-bak briefly considered intergrating the ministry into the Foreign Ministry ahead of taking office in 2008, though the plan did not materialize and he also later tapped his confidants for minister.

Shutting down the ministry has never publicly been an option for Park, who rolled out a series of ambitious bilateral and multilateral collaborative initiatives involving North Korea after being sworn in in February 2013.

As the projects unfolded, however, she opted to create new organizations such as the National Security Council and the Presidential Committee for Unification Preparation, instead of shoring up the ministry which as a result provided necessary assistance at best while regular, administrative duties remain business as usual.

With Cheong Wa Dae having now taken over the decision-making core and sanctions diplomacy kicking into high gear, the ministry’s foremost functions centering on engagement are at a standstill.

Despite Pyongyang’s unabated provocations and threats, the ministry should better remain in the background as a channel for future communications and work to firm up the foundation for unification, critics say, taking issue with Hong’s open pursuit of pressure and his agency’s newfound foray into nuclear issues.

“The pan-governmental approach aside, I believe the ministry should remain an ultimate bastion in inter-Korean relations in preparation for a thaw one day rather than speaking of sanctions and pressure,” said a government official working on North Korea affairs.

Chang Yong-seok, a senior researcher at the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University, also is concerned about the ministry’s dwindled role in line with the “all-or-nothing” hard-line drive that may expose gaps with those of the U.S., China and other stakeholders.

“Seoul has set ‘regime change’ as its goal of sanctions, far beyond denuclearization, at a time when Washington and Beijing seek dialogue as their objective,” he told The Korea Herald.

“Under the policy, the Unification Ministry would in effect be doomed to shut down. … The idea of the TF on nuclear issues seems nonsense to me.”

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)