On the wall of Korea Finance Investment Association chairman Hwang Young-key’s office in Yeouido, Seoul, is a work of calligraphy that reads: “Finance flowing through four oceans.”

The script was a gift from a descendant of Yue Fei, a Han Chinese military general, to the association, apparently giving a clear invitation for the Korean financial services industry to expand their international presence.

|

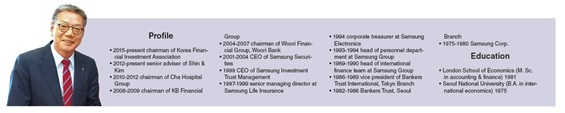

| Hwang Young-key, chairman of the Korea Financial Investment Association, poses before an interview with The Korea Herald in Seoul on Wednesday. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) |

Established in 2009 through a merger of the three associations of securities, futures and asset management firms, KOFIA serves as a nonprofit, self-regulatory body representing 312 members, mostly brokerage and asset management firms.

Hwang said Asia’s fourth-largest economy, after achieving rapid economic growth, was at a critical juncture in taking a leap forward to become an advanced capital market.

However, a big “wild dog” — a combination of factors including excessive financial regulation, some xenophobic attitudes witnessed during U.S. private equity firm Lone Star’s buying and selling of the Korea Exchange Bank and ordinary people’s fear of stock investment — is scaring away opportunities, he said.

“Following the economic growth phase, so-called financial deepening in Korea has progressed to a degree where individual and state financial wealth are largely accumulated. The economy is right in front of a door that opens an advancement of the capital market,” Hwang said during an interview with The Korea Herald.

“If Korea focuses on nurturing the asset management sector, it is possible to become an Asian hub.”

He said the nation’s asset accounts will grow to as much as 4,000 trillion won ($3.5 trillion) by 2030 from about 1,300 trillion won this year, given the fast growing public pensions including the National Pension Fund, retirement funds and personal funds.

However, such a rosy picture is feasible only if Korea can tackle heaps of challenges that have long remained a stumbling block for the financial services industry to truly advance, warned the ex-chairman of both KB Financial Group and Woori Financial Group.

In fact, critics have repeatedly said the financial sector has underperformed compared to the explosive growth of the manufacturing sector, lacking a stellar financial services provider that can be paired with big names such as Samsung.

Officials in the financial sector should first be held responsible for the sluggish progress, Hwang stressed, because they did not push hard enough to fight back against the rigid bureaucracy of the government.

“Instead, they settled ‘under the safe umbrella of labor unions,’ enjoying a life of money and comfort,” said the 64-year-old, who took office at KOFIA a year ago for a three-year term.

Hwang forecast that the local financial industry will be soon hit by an enormous external shock from so-called fintech, or financial technology, and it is up to Koreans whether to embrace it, and use it to give higher values to people and move forward as an advanced nation, or remain a mediocre country.

“No matter how hard market players try to upgrade the market, they often face strong resistance at the National Assembly. The government’s bureaucracy is so strong and usually fails to respond to the demand of the market.”

‘Koreans are natural-born bankers, financial investors’

His rather cynical view, however, is somewhat offset by his strong faith in the Korean people’s capacity to excel in finance.

Hwang gave two pieces of evidence. One is a small private banking system among relatives and close friends called “Gye,” which has been common across the country since the 1960s. The other is popular card game Go-Stop, a betting game often played at family gatherings.

“Under a Gye, a lump sum is rotated to members one by one, usually each month. In this, banking concepts such as borrowing, lending, and interest rates are all understood. Basically, Koreans are all bankers. This is quite unusual to other countries,” he said.

“When Koreans play Go-Stop or golf, they show a super-excellent ability to create so many different derivatives while playing the game. They are never satisfied with simple rules.”

He compared the Korean people’s potential in finance with that of Japan, where he worked as a banker for three years in the 1980s.

“The Japanese do not really possess ‘financial DNA’ in their blood. The Japanese financial market is still led by banks, which is a strangely an underdeveloped system. I would say Japan is like a primary schooler with a big body,” Hwang said, adding that the Japanese Finance Ministry officials’ greed for power hampers capital market growth.

Hwang said he recently saw a slight change in Korean people’s attitudes and behavior in stock investing. People used to buy and sell stocks every three to six months as a means of profit-taking. Now, however, the trading frequency has fallen to two to three years, indicating that people have come to realize that holding stocks in a certain firm is equal to having a business partnership with the company, he said.

“It will take about three to five years until this ‘equity culture’ is fully established. But I’m beginning to see it in our society.”

‘Gladiator’ spirit keeps him going

Born to a poor family in Yeongdeok, North Gyeongsang Province, in 1952 during the Korean War, Hwang has led a typical ’50s-born Korean man’s life. His parents stretched thin to move to the then-affluent district of Myeongryun-dong in Seoul to provide prestigious education for Hwang and his three siblings. He survived amid fierce competition to enter top school Seoul National University and landed his first job at Samsung Corp.

His life and world views dramatically changed in the early 1990s when he personally observed how Samsung Group chairman Lee Kun-hee strived to study hard to make his company contribute to mankind, not just make more profits.

“It was a great shock to me to watch Chairman Lee, so quiet and introverted on the surface, dig into something really deeply if it was helpful for management,” he recalled.

Hwang’s darkest moment in life came after he took office as founding chairman of KB Financial Group in August 2008. While he was busy managing the company to deal with the 2008 global financial crisis, the Financial Services Commission in early 2009 suspended Hwang for three months, saying he allegedly breached rules while making investments on collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps when he was serving as CEO of Woori Bank in 2005-2007.

He filed a lawsuit against the FSC and won the case in March 2011.

“In hindsight, I realized this was a political attack on me to take away my post. But I was sure that I could reveal the truth through a lawsuit that I did not do anything wrong,” he recalled.

“I promised myself I would make a comeback in the financial industry. Such strong belief kept me going.”

That self-promise became a reality.

In March 2015, Hwang beat out two rivals to gain the majority of the votes of KOFIA members to head the association. The media called it “the return of the gladiator.” He earned the nickname “gladiator” during his inauguration as CEO of Samsung Securities from a response to a journalist’s question as to whether he could keep his promise to put clients’ profits before those of the brokerage.

“At that time, I stood firm and replied that I would not lose this fight and I would fight like a gladiator,” Hwang said.

As an ardent reader of history, Hwang said he hopes to write a book one day to compare regional differences in financial histories and growths.

“I hope to keep brushing up on my knowledge to write about histories of financial industries which could help policymakers or financial industry officials to better design the industry, give incentives and nurture talents.”

By Kim Yoon-mi (yoonmi@heraldcorp.com)