Since stepping into politics in 2011 as a fresh alternative, former computer virus vaccine developer Ahn Cheol-soo has received fluctuating reactions from the public, varying from high hopes to utter skepticism.

Despite persisting doubts and disapproval, the information technology mogul-turned-politician at last seems to have made his mark as a heavyweight opposition figure, thanks to his party’s surprising achievement in Wednesday’s parliamentary election.

|

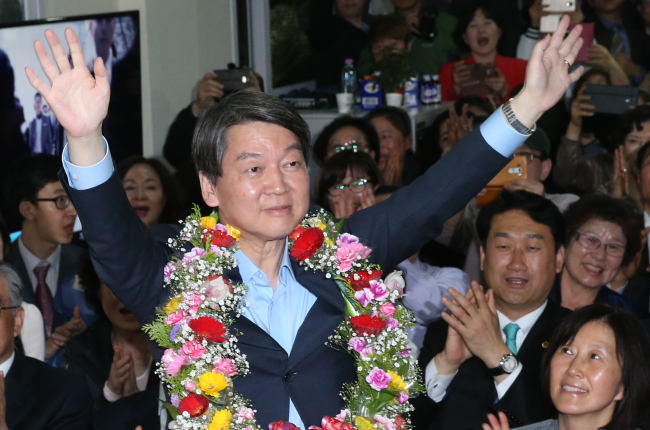

| People’s Party leader Rep. Ahn Cheol-soo reacts after winning in a Seoul district in the April 13 general election. (Yonhap) |

The fledgling centrist minority People’s Party, founded in February mainly by main opposition defectors, claimed 38 parliamentary seats in total, 25 from regional districts and another 13 through party approval ballots.

It thus crossed the 20-seat minimum required to gain a say in the National Assembly as well as its hopeful target of 35, surprising many pessimists.

As neither of the two leading parties — the ruling conservative Saenuri Party and main opposition The Minjoo Party of Korea — managed to win a parliamentary majority, it is the novice party that will hold a tie-breaking vote in the incoming legislature.

Such success seemed to justify Ahn’s much-disputed decision earlier to defect from the Minjoo Party and set up a new party of his own, bearing the blame for further splitting the opposition ahead of the election.

While steering his party during campaigning season, he also saved face by winning a consecutive term in his current Nowon-C constituency in northeastern Seoul.

This double feat is likely to expand the political leverage for the minor opposition party, as well as for the Gwangju-Jeolla region in which it scored a sweeping victory.

But it also means the party, especially leader Ahn Cheol-soo, will be facing increasing pressure to clarify its yet ambiguous policy disposition.

Considering itself a balancing weight between the top two parties, the People’s Party has been fielding a “centrist” platform, calling for a conservative view on national security issues and progressive approach on economic ones.

But so far, its detailed policies and statements have failed to differentiate themselves from those of conventional parties.

For instance, the party has listed the fair growth principle at the top of its platform, but the idea has often been criticized of resembling the economic democratization fielded by the Minjoo Party chief Kim Chong-in.

It also pledged zero-tolerance upon increasing North Korean threats and a resumption of six-party talks while arguing for the suspended inter-Korean industrial park to reopen, all of which sounded like a mishmash of positions held by the mainstream parties.

Another major obstacle for Ahn in the upcoming months is his disparity with the rest of the leadership members, most of whom are former ranking Minjoo Party figures based in the Gwangju-Jeolla areas, dubbed the “Honam” region.

When defecting from the Minjoo Party, Ahn swept along a number of Honam celebrities, rallying support from the region that has been showing signs of withdrawing its longtime support for the main opposition.

But being born in Busan and having lived in the capital area all along, the party initiator had little personal connection to the region.

It was for such reasons that he brought in Rep. Chung Jung-bae, a former justice minister and powerful figure in Gwangju, as the party’s cochief.

During the campaigning season, the two strategically divided their roles, allocating Honam to Chun and the symbolic metropolitan belt to Ahn.

Their partnership seems to have worked, going by the election results, but the two had earlier feuded over a possible reunion with the main opposition cluster.

Ex-Minjoo figures, including Chun and Kim Han-gil, were inclined toward the idea, while Ahn sternly refused to merge for the sake of election interests.

By Bae Hyun-jung (tellme@heraldcorp.com)