With a new development agenda taking off over the next 15 years, traditional and emerging donors should join forces alongside the private sector, civil society and other non-state actors to beef up financial sources and leverage inclusive growth, leading international policymakers said Tuesday.

The Korea Herald brought together four officials from around the world to explore ways to better implement the Sustainable Development Goals set forward early this year by 193 countries at the U.N.

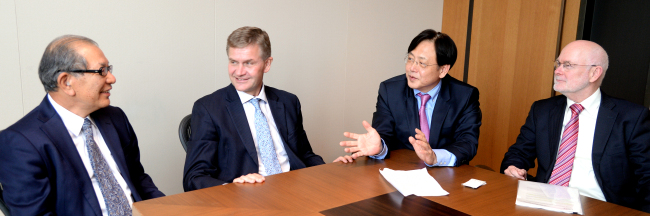

They are Erik Solheim, chair of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee; Hideaki Domichi, senior vice president at the Japan International Cooperation Agency; Jeroen Verheul, ambassador-at-large for development cooperation at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and Kim Young-mok, president of the Korea International Cooperation Agency.

The roundtable took place on the sidelines of the ninth Seoul ODA International Conference hosted by the state aid agency and the Foreign Ministry for a two-day run. Some 600 policymakers, diplomats and experts took part in the event, themed “Inclusive Partnership in the post-2015 Framework.”

In line with the theme of the forum, the participants unanimously voiced the significance of collaboration. Without bringing onboard businesses and civil society, the international community would not be able to cater to enormous demands for infrastructure development, realize the 17 goals and 169 targets and thus plug the gap between the rich and developing worlds, they said.

The SDGs are a set of targets on international development agreed upon among the governments for international development. The final document was adopted in September and includes goals to end poverty and hunger and improve health and education, all while fighting climate change and making cities more sustainable.

While lauding Korea’s stellar ascent from an aid recipient to a rising donor, they also called on the country to step up its contributions both financially and institutionally, such as by linking assistance, private investment and taxes.

The following is an excerpt of the discussion.

|

|

Participants join a roundtable on the margins of an international development aid conference in Seoul on Tuesday. From left: Hideaki Domichi, senior vice president of the Japan International Cooperation Agency; Erik Solheim, chair of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee; Kim Young-mok, president of the Korea International Cooperation Agency; and Jeroen Verheul, ambassador at large for development cooperation at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. |

The Korea Herald: In shaping the post-2015 development agenda, the role of non-DAC donors was more significant than ever. What is your blueprint for the partnership with these actors?

Erik Solheim: When you speak about inclusive partnership, I think there are two dimensions. One is that no nation can do anything on its own. Even the most influential actor, the U.S., cannot solve problems on its own ― we should solve the problems together.

Secondly, governments cannot solve the problems on their own. You need to bring in businesses, civil society and the society on the whole so that it is inclusive, with everyone on board, globally.

Let me give you one example of a successful partnership where I was personally involved. It was a very successful partnership to conserve rainforests. It was a partnership between the governments of Brazil and Indonesia, which are key rainforest nations, and key global businesses like Unilever and local pharma companies of Indonesia, and big civil society associations like Greenpeace. The companies representing 90 percent of deforestation in Indonesia came together and made a pledge that they would stop their existing practices and make profits from sustainable use of resources of Indonesia. When everyone comes together, you can achieve success.

Hideaki Domichi: We expect to see the future where more developing countries will emerge as main players and contribute to world growth. Thereby all the countries will learn from each other the best practices and think together to develop new models of development.

But at the same time, we should recognize that we have a huge international gap. Most of the multilateral development banks issued a statement jointly in Addis Ababa that now we should talk about the trillions of dollars of proposals ― public and private, domestic and international, capital and capacity-building.

What does this mean? The ODA itself will not be able to cope with all the challenges at least to make it a success. So the key issue here is how to make the ODA sources a catalyst to encourage the participation of the private sector and other stakeholders.

KH: In a few generations, Korea has made a remarkable transformation from an ODA recipient to a donor, and now it’s a member of the DAC. What does Korea have to offer to the international development community?

Kim Young-mok: Many friends are telling everybody that Korea has already made a kind of miracle, and if it can make a miracle, why not others?

So this is one thing we can offer. We do our best in IT sharing, rural development on the Saemaeul model, health care with a universal health system and education among others.

Korea’s commitment is a little bit controversial in terms of volume of financial contribution. But in terms of human engagement and people-to-people exchange and working together from the ground up, I think it is a good model because we have quality volunteers and experts who are being welcomed in many countries, along with some interesting Korean cultural wave.

Solheim: My encouragement to Korea will be to do more to step up on aid. You’re doing very well on aid, it’s fantastic, but you can do more. You need to provide more money to do more what you are good at.

If you go around the world, people know about Korea. Samsung now sells phones around the world. In every European country, you can see people driving Hyundai cars on the street. So you have very strong chain markets and global companies; to link up between aid and these companies is my encouragement for the future.

KH: Japan has a long experience as Asia’s traditional donor. Given the role of Korea and China as emerging donors, what do you think the three East Asian countries can do together on development cooperation?

Domichi: As Kim said, Korea has something to offer. And we have something to offer. How to combine our resources including knowledge and experiences, this is something we want to push forward.

Now the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is in the spotlight today. We also believe that the AIIB has been established to make some contribution to fill the big international gap. We are very much interested in how this organization will work and have global standards.

KH: Water management is one of the key areas that the Dutch government is focusing on. What is the Netherlands doing to better manage water and accomplish SDGs in general, and do you have partnership programs with other countries or organizations?

Jeroen Verheul: Indeed, access to water and managing water properly is one of the key themes of our policy. It has been for many years, because you have to develop yourself to share with others, and as Eric said, together is a key word. Of course, the Netherlands is a country with a large area below sea level, so climate change is a threat to the Netherlands as a nation.

I’m pleased to tell you that we are working together with KOICA to help Indonesia to further develop their strategy to protect Jakarta against water. If nothing happens, in 2020, they will be largely threatened by water, and that is something we want to help them avoid.

Kim: As he said, the Netherlands is good at water management, and Korea is a newcomer. … We decided to make a job division and share our experience and technical edge, so that our works do not overlap and can be complimentary.

If our job comes off successfully and something can be done to prevent the sinking of land by managing water and preventing the rise of the sea level, it will be very historic and a benchmark in terms of international cooperation.

At some point, we would welcome Japan, Britain, Australia and other countries to join and make this project a really good example of international cooperation.

Verheul: I think that this kind of cooperation shows that the dividing line between countries and organizations is fading. We talked about traditional donors, emerging, new donors, recipients, etc. But in fact the world economy is moving so fast that you cannot put a black or white label on a country or organization.

KH: At the Addis Ababa conference last July, the OECD introduced the concept of total official support for sustainable development to emphasize the partnership between various sources of finance. What’s the significance of TOSSD, and the partnership?

Solheim: The main outcome of all this was that we have completely changed the conversation about development finance. We’re working on three legs at the same time ― aid, private investment and tax. There’s no competition between the three, you can use aid to better tax or private investment.

The new system is broader than ODA but never to replace ODA. But the main step forward now is to say that if other governments, say Ethiopia or Kenya, need aid in education, for example, you need investment and domestic tax revenues for sure to pay for everything.

Domichi: The role of the private sector is key. The real question is how to defuse risks for the private sector. This is crucially important. Now the multilateral development banks including the IMF are addressing the issue.

JICA also established a private-sector investment fund. But honestly, we’re still at the stage of proving under what circumstances the public-private partnership will work best.

Verheul: He made a valid point in terms of bringing down the risks for the private sector to invest in developing countries.

Another part of the story is the business models that the private sector uses. Can those business models be adapted to promote development in countries where they’re working? That’s certainly possible.

KH: The refugee crisis that’s unfolding in Europe is posing a great global challenge. What do you think that the DAC and overall international community can do, if anything, to help tackle the situation? Do you see the need for a special fund specifically designed for refugee or similar humanitarian crises around the world?

Solheim: The main issue, which is to promote peace in Syria, is beyond what the OECD can do. What we can do is to help develop assistance to be more relevant in the refugee crisis, and support Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, which are the three neighboring countries receiving a huge amount of refugees. They deserve assistance.

The European Union has already established a special fund for Syrian refugees and discussed how to do this with Turkish leaders, so that’s moving.

What we can do is to mobilize more money for this, but we also need to protect development aid because of the strong calls for European governments to use development aid to refugees at home, which they are allowed to do according to rules but will not be beneficial.

I’ll also give advice to Korea to look into this because you are very far from Syria but very close to North Korea.

When the time of Korean reunification comes, Korea will need enormous help from outside. The amount is so huge that it cannot be funded by Korea alone ― you need China, the U.S. and the entire world when the time comes.

Verheul: We all face the dilemma. As Eric points out, the major victim may be development assistance because of its pressure on one hand, the pain for migrant children and refugees who come to those countries which are eligible for the ODA. It’s also strengthening the expenditure for refugees in the region ― the millions of refugees who are kept in the camps there ― the enormous costs that also come from the ODA, and the support for countries like Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, it’s also eligible for the ODA.

It’s the diversion of the ODA to crisis and if the ODA remains constant, it has to come from somewhere.

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)