From joining China-led financial and infrastructure initiatives to shunning the U.S-led economic sanctions against Russia, South Korea is taking an increasingly pragmatic foreign policy approach, all the while triggering concerns over the potential impact on its alliance with the U.S.

|

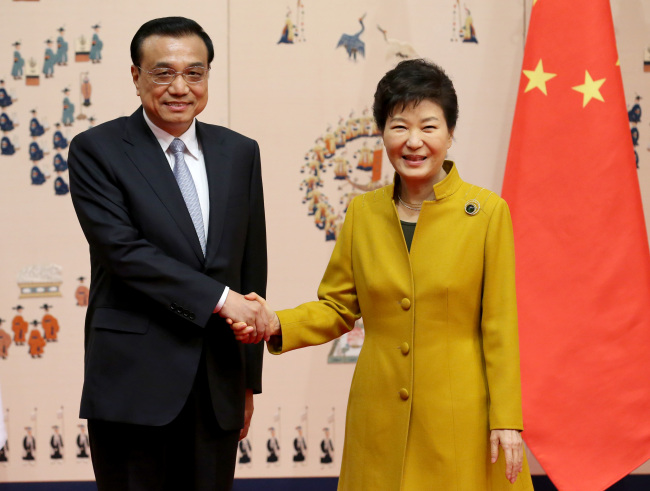

| President Park Geun-hye and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang pose for a photo before their talks at Cheong Wa Dae last week. (Yonhap) |

Analysts say that South Korea has secured more “autonomy” in its foreign policy decisions as its national power has grown amid the relative decline of the U.S. superpower status, the rise of China and the continued deterioration of North Korea’s political and economic systems.

“In the past, South Korea depended wholly on the U.S. to defend itself against the North. But now, its capabilities (both economic and military) have increased, giving rise to more room for autonomy in the Seoul-Washington alliance,” Kim Tae-hyun, diplomacy professor at Chung-Ang University.

“The U.S. is also cautious in handling its ally, South Korea, as it has experienced a set of cases that triggered deep anti-American sentiment here. The competition between the U.S. and China has also expended the space for Seoul’s diplomacy to maneuver to a certain extent.”

In the 21st-century international politics, countries have become freer in pursuing their pragmatic policy approach based mostly on interests, whereas it was difficult during the Cold War as they were forced to choose between the U.S. and the then Soviet Union.

In what analysts call a “multipolar” world consisting of multiple major countries, opportunities to pursue mutual interests have increased as many countries, economically intertwined, do not see world affairs as a “zero-sum” game in which one side’s gain means the other side’s loss, experts said.

“Based on the Cold War-era logic, you would be labeled as a betrayer or opportunist if you sought to be on good terms with both sides in different camps. But from the 21st-century viewpoint, this is only natural,” said Suh Jin-young, professor emeritus at Korea University.

Seoul has recently made a series of foreign policy decisions that apparently prioritized economic interests while paying less attention to political or alliance factors in the decision-making process.

During a summit between South Korea and China, the two sides agreed to explore the possibilities of a joint fund to support bilateral efforts to connect the two nations’ ambitious projects to link them with the world through massive infrastructure construction programs.

Seoul’s project is called the Eurasia Initiative, while the Chinese one is called “One Belt One Road.” Washington has apparently seen Beijing’s high-profile project as a long-term plan to expand China’s sphere of influence.

Seoul has also opted not to join the U.S.-led economic sanctions against Russia, which were slapped on the country after the Ukraine crisis last year. It has also joined the China-led Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, an institution that some U.S. scholars say could challenge U.S.-led financial institutions such as the World Bank.

The South was also seen leaning toward pragmatism when it chose to buy four aerial refueling tankers from a European company in June, despite the rampant speculation that it would choose to purchase American tankers in consideration of its alliance with the U.S.

South Korea is not the only one that has been pursuing interests over political relations. Britain has also been seen moving closer to China as it joined the AIIB and described its ties with China as being in a “golden era.”

“Considerations of economic interests are also very important for national security. If your economy is broken, that could be as dangerous as being broken by a military conflict,” said Chun In-young, professor emeritus at Seoul National University.

Observers stressed the need for Seoul to establish a firm foreign policy identity and strategy, to help countries around the world understand South Korea’s diplomacy and prevent them from looking at it with suspicion.

“Seoul needs to have a firm strategy based on national interests and proclaim it to the world. This could be a middle-power strategy. Otherwise, dissenters would say South Korea is double-faced or its policy is sort of oscillating and unreliable,” said Kim of Chung Ang University.

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)