After 24 years of relentless squabbling, Seoul has managed to pull off a compromise to put an end to the issue of Japan’s sexual enslavement of Korean women during World War II ― with perhaps the most unlikely leadership of hawkish Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

But the ongoing furor is showing little sign of abating, chiefly over Seoul’s failure to consult with the aging victims before last week’s surprise announcement. A string of protests have since begun in the capital and are poised to spill over into the U.S., Europe and other regions.

The rampant public indignation appears to be merely the beginning of what may be mounting challenges that will keep coming back to torment Korea’s diplomacy in the coming years, if not decades.

|

|

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivers a speech at the National Diet in Tokyo on Wednesday. (AFP-Yonhap) |

At stake is the foundation to be set up here with 1 billion yen ($8.4 million) from Japan, to be run by Korea. Seoul officials have boasted the idea as their “innovative” brainchild that makes Tokyo’s compensation official, albeit in a roundabout way.

In reality, the Foreign Ministry here willingly made way for the Abe administration to dilute its responsibility. If ministry negotiators were to sell the funds as de facto reparations, they should have persuaded their Japanese counterparts to directly offer money to the victims, whatever title it may carry.

With no details having been established, humanitarian assistance, medical support and other programs alike seem a no-brainer for those who will operate the foundation. Then it would be no better than the unsuccessful proposal navigated in 2012 by the two countries, the “Sasae formula,” named after Japan’s then-Vice Foreign Minister Kenichiro Sasae.

Even if Korea opts to give part of the promised cash to the victims as redress, Japan will likely maintain that the decision was made by the foundation to which it simply transferred the money, and thus does not imply legal responsibilities.

The outlook also remains gloomy for the envisioned entity’s self-sustainability.

The 1 billion yen may seem a large figure, but in an era of ultralow interest rates, the organization would have to operate on an annual budget of some 200 million won ($170,000). That could prompt the Korean government to funnel more of the promised “administrative costs” to finance rent for office space, employee salaries and other expenses, turning the foundation into something similar to a mutual fund, another feat for Japan.

On the agreement’s conditions, Japan’s duty has backtracked from previously failed measures ― it virtually needs to pay only money ― whereas Korea is bound by its pledge not to bring up the sex slavery issue again on the world stage, as well as to explore a possible relocation of the “comfort woman” statue in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

This means when Korean activists and scholars detail the Japanese Imperial Army’s vicious sexual violence against the women in frontline brothels at the U.N. or other venues, ministry representatives, who had lambasted the moves as a breach of “universal human rights,” will now have no option but to stay mute.

Take the Sasae formula ― the negotiations eventually broke down because Japanese officials rejected Seoul’s demand that they would not publicly disavow the deal such as before the parliament, according to diplomats who were involved in the process. This time, no such strings are attached.

|

|

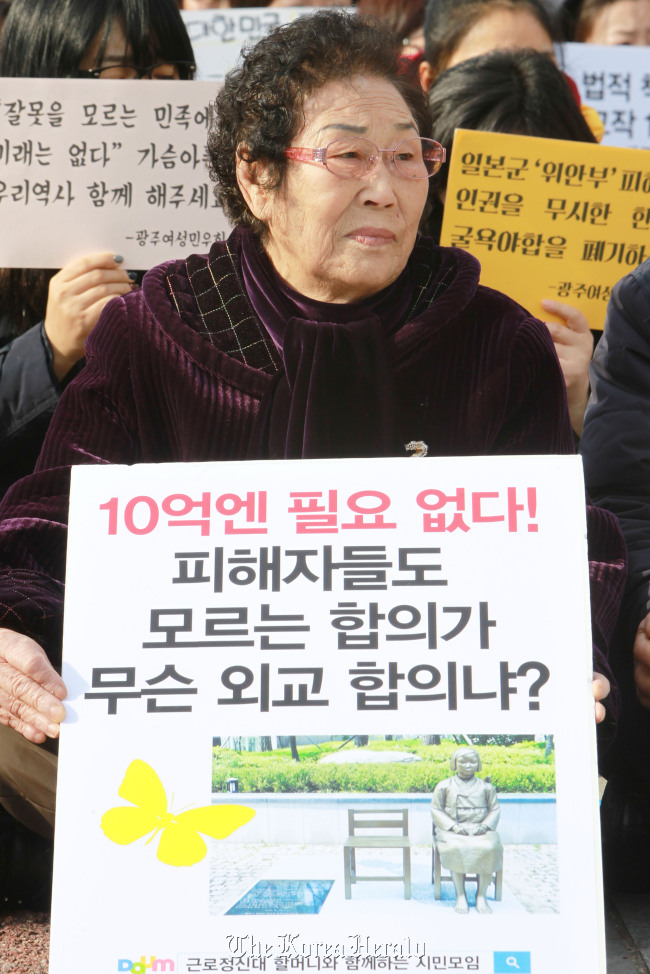

Former comfort woman Yang Geum-deok participates in a protest in Gwangju on Wednesday against Seoul`s recent agreement on Japan`s wartime sex slavery. (Yonhap) |

In further backpedaling, Tokyo did not address the involvement of the government in the conscription of “comfort women” during the war, though it admitted to “state responsibility” for its military’s brutalities.

The Kono Statement, a watershed 1993 apology issued by then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono that Abe has since sought to water down, did acknowledge and apologize for the participation of both the military and government in operating “comfort stations.”

The deal may be the best that Seoul can yank from the country ruled by a revisionist premier who has repeatedly striven to whitewash its wartime atrocities, as diplomats argue. But their claim rather intensifies questions as to why they had to hasten the bargain while deserting the longstanding principle that any settlement should be acceptable to the victims and convincible for the public.

The rushed negotiations, and the resulting criticism, appear to be a self-incurred diplomatic debacle. Emboldened by Abe’s visit to the controversial Yasukuni war shrine in December 2013, the Park Geun-hye administration had until early this year pushed with a hard-line approach toward Tokyo without any behind-the-scenes talks or thorough “exit strategy.”

Its stretched Japan-bashing soured domestic sentiment toward a close neighbor and key trade partner, taking a toll on bilateral diplomatic, economic and people-to-people exchanges, while creating “history fatigue” in Washington and skepticism that Seoul was leaning more toward Beijing and hampering crucial three-way security cooperation in the face of evolving North Korean threats.

“The agreement’s overall unsustainability resulted from Korea’s lack of strategy for Japan ties and also the sex slavery negotiations. The administration had set a trap by pressing ahead with a tough line toward Japan, apparently in the pursuit of domestic political interests, but without taking into account a bigger regional landscape including the U.S.’ Northeast Asia strategy, and then fell into that very trap and faced isolation,” a diplomatic source said, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

“The ministry would have wrapped it up a lot better if it attached the provision after concluding the negotiations saying the final decision is up to the victims and requesting their consent.”

Given the intensive sensitivity of the history issues and deeply dampened public feelings toward the Abe leadership, for which the Park government has no one but itself to blame, its officials should make constant, utmost efforts to have Tokyo follow through on its commitments and refrain from any more attempts to undercut the deal.

In the short term, they ought to focus on appeasing the furious victims and public through sincere talks and coming clean about the negotiations to shake off persistent doubts about a possible backdoor arrangement involving the monument or a deferral of the envisioned UNESCO listing of comfort women documentation. For the foundation to truly cater to their wants and ward off further backlash, the women and their advocates must be invited for advice in the run up to its launch at least, or preferably become part of the steering committee.

And the task is not for vice foreign ministers. It is for Foreign Minister Yun Byung-se and the president herself.

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)