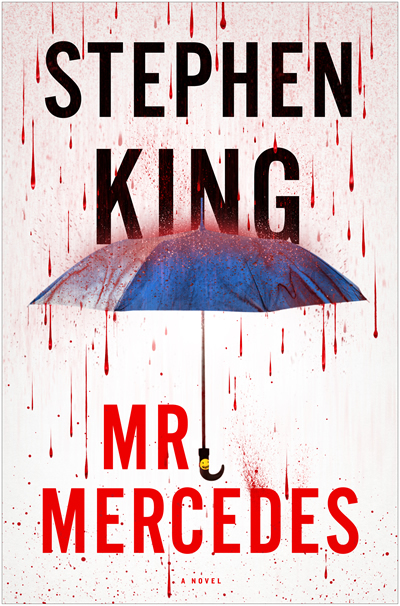

In “Mr. Mercedes,” Stephen King gives the ghosts and ghouls a rest and returns to the non-supernatural suspense genre of such earlier novels as “Cujo” and “Misery.” He also resists the bloat that has crept into his books over the last decade, keeping the story moving at lightning speed ― I dare you not to read the last 100 pages in one sitting ― and focusing primarily on two characters, antagonists about to embark on an elaborate dance of wits.

In “Mr. Mercedes,” Stephen King gives the ghosts and ghouls a rest and returns to the non-supernatural suspense genre of such earlier novels as “Cujo” and “Misery.” He also resists the bloat that has crept into his books over the last decade, keeping the story moving at lightning speed ― I dare you not to read the last 100 pages in one sitting ― and focusing primarily on two characters, antagonists about to embark on an elaborate dance of wits.

One is Bill Hodges, a retired 62-year-old detective who is divorced and estranged from his only daughter. Bill spends his days on his La-Z-Boy, watching reality TV shows and playing with his .38 Smith & Wesson. Occasionally, he sticks the barrel of the gun in his mouth, but he hasn’t yet reached the point at which he’s ready to pull the trigger. After years of active duty, he’s depressed and bored and feels obsolete but not yet suicidal. He’s getting there, though.

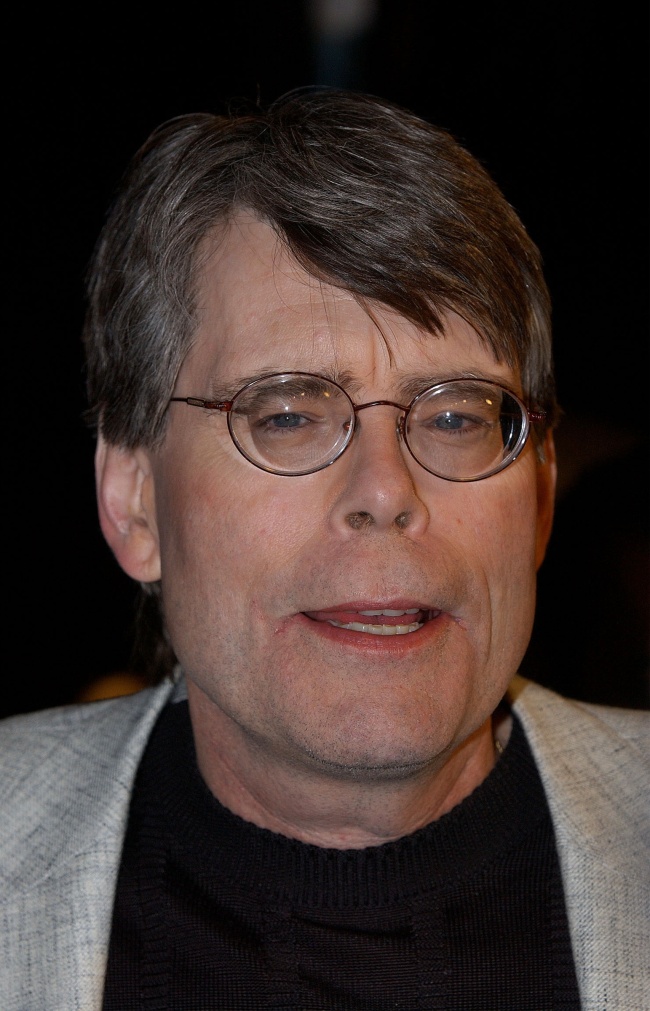

|

| Stephen King (MCT) |

The other is Brady Hartfield, a “genetically handsome fellow with neatly combed brown hair and a bland say-cheese smile” who a few months prior rammed a stolen gray Mercedes into a crowd of unemployed people waiting in line at a job fair (the story is set in 2009, the economic depression playing a supporting role). He killed eight people, including a baby, but was never apprehended.

Hodges is haunted by the unsolved case. Hartfield, who lives with his alcoholic mother and holds down two jobs (computer repairman and ice-cream truck driver), is a psychopath so twisted he got a sexual kick out of mass slaughter and can’t stop reliving it.

“I still relive the thuds that resulted from hitting them, and the crunching noises, and the way the car bounced on its springs when it went over the bodies. … When I saw in the paper that a baby was one of my victims, I was delighted!!! To snuff out a life that young! Think of all she missed, eh?” Hartfield taunts Hodges in a letter that kick-starts the plot.

King is the Woody Allen of bestselling writers: He cranks out a book a year, sometimes two (another one, “Revival,” is due in November). “Mr. Mercedes” feels like something he wrote as quickly as the novel reads ― the simple plot unfolds over a couple of days and could be summarized on a post-it note ― but it’s also a superb example of how the writer hooks you by getting into the minds of his everyday protagonists. The book is peppered with contemporary pop-culture references that give it a veneer of veracity: iPads, Dexter, online dating sites, boy bands with lead singers who sound like “Jim Morrison after a prefrontal lobotomy.”

But the real hook in “Mr. Mercedes” has long been King’s strongest weapon: His ability to allow us to inhabit his characters so fully, we feel like we’re seeing the world through their eyes. That’s true of the likable cop, a typically noble and responsible hero whose only apparent flaw is a bulging waistline (King’s good guys tend to be angelic enough to merit halos).

The most fascinating character in “Mr. Mercedes,” though, is the twisted, broken Brady, a computer genius whose creepy relationship with his mom makes Norman Bates seem like a model son. Some of Brady’s inner monologues bear an uncanny resemblance to the testimonials and taped YouTube farewells left behind by real-life killers before they headed out on a rampage ― people, usually men, whose self-pity curdles into anger and murderous hatred.

As he prepares to commit his next act of mass murder, the pathetic Brady contemplates who is responsible ― anyone but him. “He’s not worried about God, or about spending eternity being slow-roasted for his crimes. There’s no heaven and no hell. Anyone with half a brain knows those things don’t exist. How cruel would a supreme being have to be to make a world as (messed) up as this one? … Can he be blamed for striking out at the world that has made him what he is? Brady thinks not.”

“Mr. Mercedes,” which was written last year, feels like it was inspired in part by tragedies such as the shooting in the Aurora, Colorado, movie theater and the school killings at Sandy Hook. What drives seemingly sane people to do such barbaric things? Sadly, the book arrives on the heels of another murder spree by a social outcast in Santa Barbara, California. Others will inevitably follow.

But King doesn’t exploit these cases for entertainment, nor does he treat the loss of human life lightly (neither does he engage in the national gun debate, practically avoiding firearms altogether). This is a taut, calibrated thriller that only occasionally veers into manipulation and sentimentality. The majority of the book is merciless and unforgiving, and the scariest thing about it is how plausible the whole scenario is. “Mr. Mercedes” isn’t scary the way “The Shining” and “Salem’s Lot” were ― you can’t even call it a horror novel, really ― but it’s chilling and compelling in a manner King’s later books often weren’t, because this one feels like it could happen. Here there be monsters, and they look just like you and me.

By Rene Rodriguez

(The Miami Herald)

(MCT Information Services)