She hasn’t decided yet.

Or if she has, she’s not telling.

But if Hillary Rodham Clinton does run for president in 2016, her new book “Hard Choices,” a chronicle of her four years as secretary of State, leaves no room for doubt about how she might conduct foreign policy (pragmatically), how she will defend herself against charges that she mishandled the attack on the American compound in Benghazi, Libya (robustly) and about how much she regrets giving President George W. Bush carte blanche to wage war against Iraq (deeply and eternally).

Other regrets: Her inability to persuade President Barack Obama to arm the Syrian rebels early on in that country’s devastating civil war, failing to act more forcefully to support Iran’s pro-democracy demonstrators during the Green Revolution in 2009, and wrongly believing that Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who resigned after weeks of convulsive protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, was “stable.”

“Hard Choices” is a richly detailed and compelling chronicle of Clinton’s role in the foreign initiatives and crises that defined the first term of the Obama administration ― the pivot to Asia, the Afghanistan surge of 2009, the “reset” with Russia, the Arab Spring, the “wicked problem” of Syria ― told from the point of view of a policy wonk.

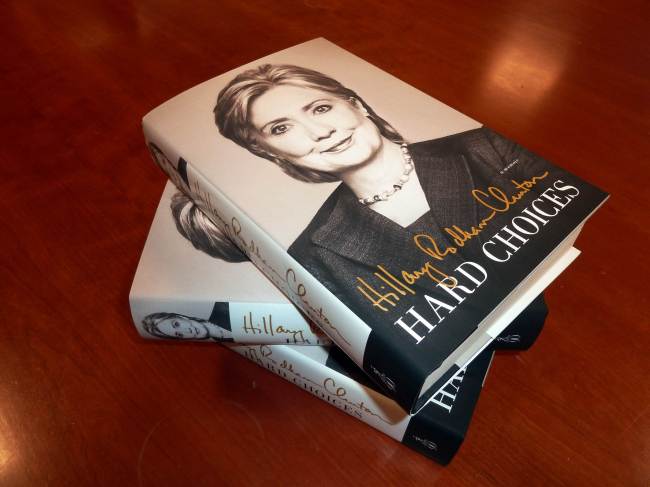

|

| Former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s memoir titled “Hard Choices” was released Monday. The long-awaited book is seen as an unofficial start to her expected 2016 presidential run. (AFP-Yonhap) |

“We needed a new architecture for a new world,” she writes of her mission as American’s diplomat in chief, “more in the spirit of Frank Gehry than formal Greek classicism.”

The dichotomy between “hard power” and “soft power” would no longer do. The Clinton doctrine, if one can be said to exist, is “smart power,” a way of combining all the tools at hand ― diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal and cultural, to effect American goals. And of course, social media. (At her urging, Michael McFaul, the U.S. ambassador to Russia, used his Twitter feed to become one of Russia’s most influential online voices.)

In country after country during four years of relentless travel, she depicts herself as decisive and cagey with world leaders, and determined to reach beyond government officials and their choreographed diplomatic meetings to interact with everyday people who might be inspired to pursue American-style democracy after an interaction with the down-to-earth secretary of State.

Clinton is well aware of her place in history, and her potential place, as well. She is still subjected to the “persistent double standard applied to women in politics ― regarding clothes, body types, and of course hairstyles ― that you can’t let derail you.” And, in what may be the worst double standard of all, she knows that she is not allowed to complain about it.

“Smile and keep going,” she advises, which may sound a little wimpy, but after living in the political meat grinder as long as she has ― as the wife of a two-term president and an elected politician in her own right ― she knows that even a twinge of anger is perceived as self-pity, and that’s verboten for women.

Those who have been following Hillapalooza, aka the roll-out of “Hard Choices,” probably know that the chapter she devotes to the September 2012 attack on the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi was leaked to Politico more than a week before the book’s publication date Tuesday. That’s as good a barometer as any that the book is a prelude to a presidential campaign.

In that chapter, destined to be the most scrutinized of her book, her well-known stubbornness and impatience with what she perceives as political gamesmanship are on vivid display. Earlier in the book, in a passage about her regrettable vote to authorize the Iraq invasion, she writes, “In our political culture, saying you made a mistake is often taken as weakness when in fact it can be a sign of growth for people and nations. That’s another lesson I’ve learned personally and experienced as Secretary of State.”

Thus, Clinton takes responsibility, but refuses blame, for the deaths of four Americans, including U.S. Ambassador to Libya Chris Stevens. She faults inadequate security, and places the tragedy in the context of global anti-American demonstrations that followed the release of an American-made video that denigrated Islam.

“I know there are some who don’t want to hear that an internet video played a role in this upheaval,” she writes. “But it did.”

Her famously testy answer to Wisconsin Republican Sen. Ron Johnson during a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on Benghazi ― “What difference at this point does it make?” ― will be used against her by partisans trying to portray her as callous or dishonest about what happened that night. In her 33-page chapter, she takes pains to put the line in context; it was a response to those who insist the administration’s talking points about the attacks in the days that followed were misleading or incorrect.

“There is a difference between unanswered questions, and unlistened to answers,” she writes. “I will not be a part of a political slugfest on the backs of dead Americans. … Those who insist on politicizing this tragedy will have to do so without me.”

She writes that she was genuinely surprised when Obama, her rival in the bitter 2008 Democratic presidential primary, chose her as secretary of State. But their reconciliation had begun months earlier, on June 5, 2008, even before his official nomination, when they met over Chardonnay at the Washington home of California U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein. “We stared at each other like two teenagers on an awkward first date,” she writes.

They had a candid discussion of what she calls a “long lists of grievances” about each other. But this hatchet was important to bury; Obama needed her help in the general election, and he needed Bill Clinton’s help, as well.

She was confident enough about her relationship with the president that in 2010 when unnamed White House staffers told her to fire Richard Holbrooke, her special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan, whose blustery style and penchant for publicity offended them, she rebuffed them and insisted on hearing it from the president himself. She persuaded Obama to let her keep Holbrooke, who died of a ruptured aorta in December 2010.

She stood her ground in other ways too. In 2008, she writes, she refused an Obama campaign request to denigrate the selection of Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as John McCain’s running mate: “I was not going to attack Palin just for being a woman appealing for support from other women. I didn’t think that made political sense, and it didn’t feel right.”

She and the president became so comfortable with each other that during a trip to Prague, she writes, the president pulled her aside. She thought he had some sensitive policy matter to discuss. “You’ve got something in your teeth,” he said.

She tells of only one dressing-down by Obama, who was angry that an American envoy to Egypt, a man she had brought to the job, publicly discussed his differences with the White House over how to handle Mubarak. Obama, she writes, felt world leaders were getting a mixed message from Americans, and “took me to the woodshed.”

Clinton’s blunt charm goes hand-in-hand with an impressive sang-froid, in her telling. When some White House advisors suggested postponing the Navy SEAL raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan because it was planned the same night as the White House Correspondents’ Assn. dinner, she writes, “I’ve sat through a lot of absurd conversations, but this was just too much. … Some in the media have quoted me using a four-letter word to dismiss the Correspondents’ Dinner as a concern. I have not sought a correction.”

Nor did she fret about Pakistan’s predictable rage at not being informed about the raid ahead of time. “Our relationship with Pakistan was strictly transactional, based on mutual interest, not trust,” she writes. “It would survive.”

The prose of “Hard Choices” may not have the soaring quality of a transcendent political speech ― there’s no language on par with her famous “18 million cracks in the glass ceiling” concession speech in 2008, but it’s also mercifully free of the bromides that mar most campaign biographies.

The book teems with small, entertaining details about her interactions with foreign leaders. When the Obama administration decided to “pivot” to Asia, ending years of what one Asian diplomat called “diplomatic absenteeism,” not every country was thrilled. “Why don’t you pivot out of here?” suggested Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo, exasperated at how the U.S. had orchestrated a challenge by other Asian countries to China’s South China Sea territoriality.

As Burma began making small steps toward democratization, Clinton asked a Burmese official if he’d been reading books or consulting experts. “Oh no,” he replied. “We’ve been watching ‘The West Wing.’”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel presented Clinton with a framed copy of a newspaper that featured a large photo of the two leaders, in identical pantsuits, with their heads cropped out. The newspaper challenged readers to guess who was who.

Clinton’s lifelong commitment to improving the lives of women and children is a thread that runs through every chapter. (One of her first jobs out of law school was staff attorney for the Children’s Defense Fund. Her first book, the bestseller “It Takes a Village,” focused on the importance of social infrastructure to families.)

She quietly intervened when Saudi Arabian courts upheld the marriage of an 8-year-old girl to a 50-year-old man. “Fix this on your own, and I won’t say a word,” she told the Saudis. A new judge approved the divorce. In a Congolese refugee camp, she learns that there is no school. “That drove me crazy,” she writes.

This memoir is a valuable account of Clinton’s time as America’s chief diplomat. It could remain just that ― a chronicle for students of history and politics. Or it could become a political document, used to persuade voters she’s fit to be leader of the free world.

Whatever she decides about 2016, no one can say she’s unprepared for the job.

By Robin Abcarian

(Los Angeles Times)

(MCT Information Services)