The book came in on two rolls of microfilm ― an unusual way to submit a literary manuscript. Then again, the recipient was not your ordinary publisher: It was the CIA, the year was 1958, and the agency was about to lob a grenade onto the battlefield of the cultural Cold War.

The grenade was “Doctor Zhivago,” by Russian writer Boris Pasternak. It would be his only work of fiction, but the controversial circumstances of its publication would spark a furor in the Soviet Union, where it was officially banned. The CIA, looking to score a propaganda coup in the war of ideas between capitalist West and communist East, spearheaded the publication and dissemination of a Russian-language edition, which made its way back into the Soviet Union.

|

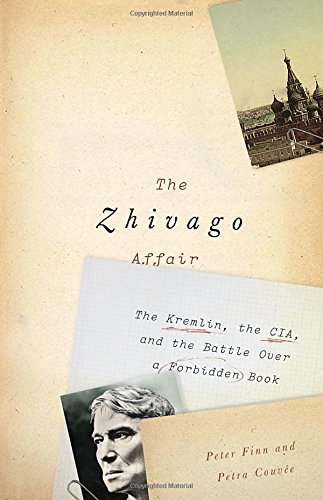

| “The Zhivago Affair” is written by Petter Finn, National security editor and former Moscow bureau chief at the Washington Post and Petra Couvee, writer and translator who teaches at St. Petersburg State University. (Pantheon) |

In their thrilling new account, Peter Finn and Petra Couvee tell the remarkable story of how “Doctor Zhivago” became a literary phenomenon. “The battle over the publication of ‘Doctor Zhivago’ was one of the first efforts by the CIA to leverage books as instruments of political warfare,” the authors write. (From the 1950s until 1991, the CIA would distribute 10 million books and periodicals in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.) Deftly combining biography, cultural history and literary tittle-tattle, they have shone a light on a shadowy operation.

Rumors of CIA involvement swirled around “Zhivago” for decades, but Finn, national security editor of The Washington Post, and Couvee, a translator and teacher at St. Petersburg State University, have proof in the form of 135 recently declassified CIA documents.

In 16 tightly packed chapters, brimming with documentation and reconstructed conversations, the authors weave together the strands of Pasternak’s life and literary struggles. Pasternak was one of Russia’s most acclaimed poets when he got around to writing “Zhivago” in the years just after World War II. He survived the grim Stalin years relatively unscathed. Some said he was a bootlicker; for a time, Stalin held Pasternak in thrall, but the writer grew to loathe Stalinism.

“Doctor Zhivago” put him on a collision course with the regime of Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, and with the Soviet literary establishment. It is very much a poet’s novel, a rambling and expansive narrative of the titular character’s spiritual odyssey through revolutionary tumult and beyond; like “War and Peace,” it is one of those populous Russian novels where too much happens. (The authors treat the book as a masterpiece, though today the book seems more admired than read.)

By 1956, after he finished it, it was clear Pasternak could not publish in the Soviet Union. Word had spread about his activities, and the secret police and literary gatekeepers were all over him. Enter an enterprising Italian Communist and literary scout in the employ of publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who secured the global rights. Copies of the manuscript were rushed into translation in France and Great Britain. MI6 passed a copy on to the CIA, though it is unclear where British intelligence procured its copy. Publication abroad was illegal; but Pasternak, invoking Pushkin, said he wanted his work to “lay waste with fire the hearts of men.”

It was a smash hit in the West ― in the United States, it toppled “Lolita” from the bestseller list, irking Vladimir Nabokov, who thought “Zhivago” was trite nonsense. The CIA saw to it that Russians would read the book in its original language, contracting with a Dutch publisher to print Russian language copies, which were then distributed at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, to which thousands of Russians had flocked.

(The United States could not be tied to the effort, so copies were handed out at the Vatican pavilion.) Later, miniature paperback copies, printed on featherweight paper, also made their way into Russian readers’ hands when they were passed out during a 1959 Vienna youth festival.

The closing sections of “The Zhivago Affair” are crushingly poignant, as literary triumph turned to tragedy. Pasternak was irked by the Russian edition, which was littered with errors. (Feltrinelli sued the Dutch publisher for rights infringement, which generated the wrong kind of publicity.) The award of the 1958 Nobel Prize in Literature, which Pasternak was forced to turn down, provoked the full fury of the Soviet state; Pravda called him a “weed.”

His mistress was harassed and jailed. Already in ill health, Pasternak died in 1960. Still, the forbidden “Doctor Zhivago” had already done its work: At the writer’s funeral, a mourner read a poem included in the novel, and, the authors write, “a thousand pairs of lips began to move in silent unison.”

By Matthew Price

(Newsday)

(MCT Information Services)