Gazing at portraits created during the Joseon era, one is struck by the extreme delicacy with which the models’ facial features are depicted, from the fine wrinkle lines to tiny spots and faint scars.

Lee Sung-nack, a board member at the Kansong Art and Culture Foundation, spotted such sophistication in the centuries-old portrait paintings and suggested that the portraits reflect signs of medical conditions that the subjects may have suffered.

A dermatologist and professor who earned a doctoral degree in art history at Myongji University in 2014, Lee began examining the skin of subjects in portraits after taking a class that studied skin diseases found on portraits at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1964.

After spotting a Joseon-era portrait that showed a symptom of a skin disease, on display at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, he delved into a study that incorporated historic art and dermatology, driven by curiosity over the intricacy of such portraits.

|

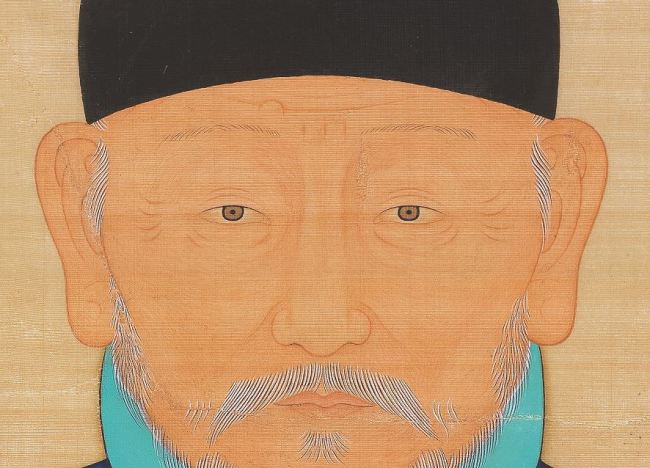

| A portrait of Yi Seong-gye, founder of the Joseon Kingdom, shows a lump above his right eyebrow. (Nulwa) |

Lee, 80, recently published a book titled “Joseon Dynasty Portraits: Expression of Scholar Spirits.” In the book, Lee says that portraits from the Joseon era depicted their models without beautification, a huge difference from those of other countries which, in an effort to glamorize and glorify subjects, rarely show facial imperfections. And those realistic portraits of the Joseon era showed many signs of skin diseases, he added.

“The fact that I was able to make a clinical diagnosis with those portraits means that the paintings are extremely delicate and accurate. Such style of painting is rare in the history of art, where portraits were often beautified for glamorization,” Lee told The Korea Herald.

During the Joseon era, portraits were considered the exclusive domain of high government officials and kings, who used the paintings to highlight their authority.

After examining a total of 519 portraits from the Joseon era with dermatology experts Bang Dong-sik of Yonsei University and Lee Eun-so of Ajou University, Lee found about 20 kinds of skin diseases in 268 pieces — nearly 75 percent of the portraits in question.

|

| A portrait of a high-ranking government official named Oh Myung-hang shows a symptom of lcterus melas, a dark discoloration of the skin due to terminal liver cirrhosis. (Nulwa) |

|

| A portrait of a high-ranking government official named Song Chang-myung shows a symptom of generalized vitiligo, a skin condition in which patches of skin become whiter from losing pigment. (Nulwa) |

The most frequent disease detected was acquired melanocytic nevus, commonly known as moles, which were found in a total of 113 pieces. It was followed by senile lentigo, benign pigmented flat spots on sun-exposed skin in the elderly, and smallpox scars, found in 85 and 73 paintings, respectively.

Symptoms for rhinophyma, a condition that causes the development of a large, bulbous nose, and lcterus melas, a dark discoloration of the skin due to terminal liver cirrhosis, were shown in some portraits of Joseon era government officials.

Generalized vitiligo, a skin condition in which patches of skin become whiter from losing pigment — which had plagued pop legend Michael Jackson in more recent times — was detected as well. Lee found out from historical records that those people had actually suffered from the aforementioned diseases.

Even the portrait of the founder of the Joseon Kingdom showed a small lump, medically known as nevocellular nevus, above the right eyebrow. And such a painting, which clearly shows a facial flaw, would not have been possible without the king’s consent, said Lee.

What Lee seeks to draw from the portraits is the “spirit of ‘seonbi,’” the zeitgeist of the period that emphasized austerity and honesty.

|

| A portrait of a high government official named Hong-jin shows a symptom of rhinophyma, a condition that causes the development of a large, bulbous nose. (Nulwa) |

“Seonbi” refers to Joseon-era scholars who did not seek monetary gain or mundane pleasures.

“During the Joseon era, there was a rule that portraits should portray every detail of a model. Allowing their portraits to show almost everything in the most realistic and honest way, regardless of their social status, I would call it a spirit of seonbi,” Lee said.

And the fact that those suffering from skin diseases ascended to high ranks in the government reflects the spirit of tolerance that prevailed in society, he said.

Lee also hopes Koreans will have more pride in their cultural assets.

“The last thing I want to emphasize is that we should have pride in our portraits. Throughout the 518 years of the Joseon period, the artistic style of portraits didn’t change once. And that’s totally unprecedented in the history of art around the world. Our ancestors, they had that spirit of scholars for a very long time,” he said.

By Hong Dam-young (lotus@heraldcorp.com)