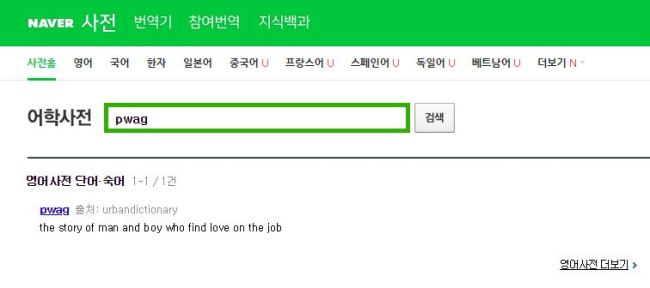

When the pseudonym used by North Korean leader Kim Jong-un in forged passports was revealed in the media last month, those who searched online for “Josef Pwag” may have found an unusual match in Naver Dictionary.

According to the site, “Pwag” refers to “the story of a man and boy who finds love on the job.” But the problem is “pwag” is neither a real word nor slang in English.

This is not the only odd — sometimes fake — piece of vocabulary defined by Naver Dictionary.

Definitions provided by the platform can range from vulgar to bizarre and inappropriate.

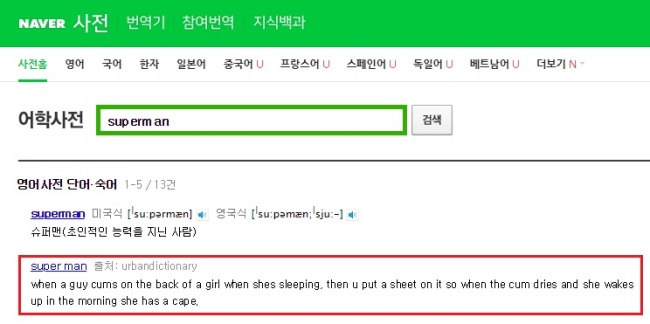

Take “superman” for instance. Among the definitions provided by Naver Dictionary is a graphic description of a post-coital sexual practice involving bedsheets. Those who wish to know the full details can look it up for themselves.

Though it is at least genuine sexual slang, its inclusion in a dictionary for foreign English learners is debatable.

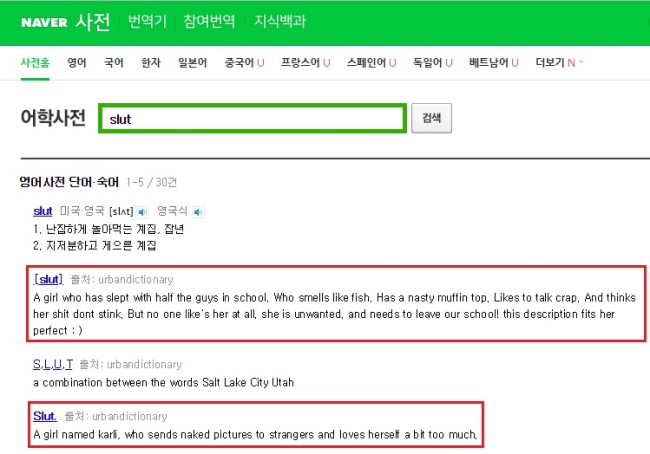

Other definitions are more off the books. Provided by what appears to be teenagers bashing their classmates, Naver Dictionary includes a definition of “slut” as “a girl named Karli, who sends naked pictures to strangers and loves herself a bit too much.”

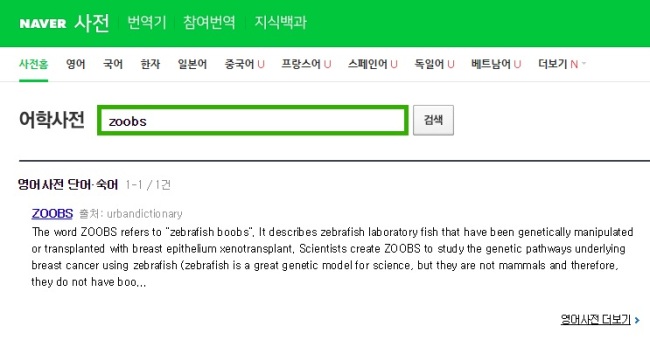

Some are downright bizarre. “Zoobs” is apparently short for “zebrafish boobs” describing laboratory zebrafish that have been genetically transplanted with breast implants for the purpose of breast cancer research.

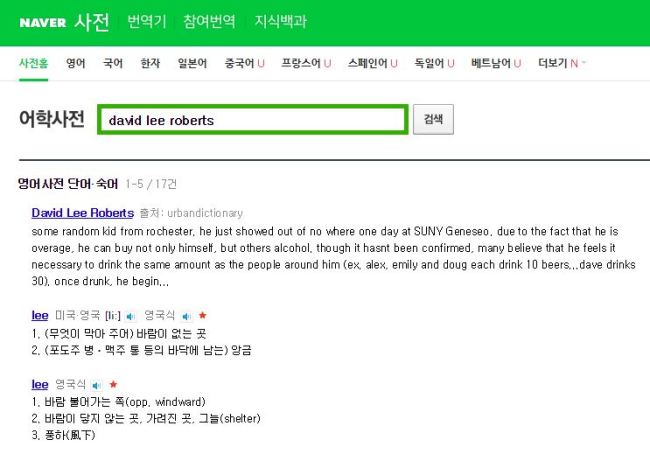

And there are countless more to the list, be it “oub,” which apparently stands for “overload of ugly b——,” or “David Lee Roberts,” who is not a prominent figure, but “some random kid from Rochester who showed out of nowhere one day at SUNY Geneseo.”

There will always be strange things on the internet. But, how did squabbles between US teenagers end up in South Korea’s most widely-used English dictionary, accessed by both kids and adults studying English?

More info the better?

According to Naver, its dictionary platform has partnered with five professional dictionaries — including Oxford Dictionary, Donga Publishing, YBM, Kyohak and Supreme — to provide definitions covering standard English.

For specialized terms related to areas like medicine and science, Naver Dictionary has partnerships with other database providers. It also operates a crowdsourced dictionary, called Open Dictionary, built by users of Naver.

It also brings in words from crowdsourced dictionary websites, such as Urban Dictionary and Wiktionary, to provide definitions of new or slang terms that standard dictionaries are slow to incorporate.

Naver insists that it has an internal filtering system to weed out inappropriate definitions sourced from external sites, but said that ultimately it believes in the value of diversity and making as much information available to users as possible.

“Naver is an online dictionary, and the internet is built on the value of ‘diversity.’ We want to let users know that there are such kinds of information on the web. And there is greater value offering access to a wider range of information, and letting the users decide what to take in,” a Naver spokesperson told The Korea Herald.

“Language is something that changes with sociocultural changes in society. Words change over time and it’s the job of online dictionary services like us to reflect the changes into our service,” the spokesperson said.

What about reliability?

While sources like Urban Dictionary do expand the database, should a mainstream dictionary like Naver’s — positioned as a reliable language learning tool — be using them?

Even Urban Dictionary (or a frustrated volunteer editor) defines itself as: “A place formerly used to find out about slang, and now a place that teens with no life use as a burn book to whine about celebrities, their friends, etc., let out their sexual frustrations” and more.

As a result, its listings are filled with words that aren’t in meaningful use, like “pwag” and “zoobs.”

“Naver Dictionary revealing what looks to be very inappropriate results is not only degrading its own quality, but also very contradictory on every level,” said 28-year-old Kim Gyu-min, an English writing and debate coach in Seoul, when told about this phenomenon.

“As a platform that provides an ‘official’ dictionary tool and apps for people to download, Naver has a minimal duty to guarantee a certain quality of service to the standard public. Besides, Naver Dictionary aims to be very different from the Naver search engine, and thus the excuse that it is merely showing search results neglects its own stance in providing this tool as an official language dictionary tool.”

Similar concerns were voiced by Korean parents, whose children use Naver Dictionary to look up English words while studying.

“In this day and age, I understand our children obviously get access to a sea of information that we can’t control. But I think it’s obvious that we expect only proper, accurate definitions to be included in an official dictionary like Naver Dictionary,” said Lee Kyung-min, the mother of a 13-year-old daughter.

“I think a formal dictionary platform like Naver Dictionary should prioritize reliability rather than diversity, considering the needs of the population using the platform. Doesn’t the open web already cover the diversity portion pretty well?”

Nam Won-jun, an associate professor of English translation at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Korea’s top academic institution in the translation domain, warned that Naver’s English-Korean dictionary “should not be fully trusted, and referred to only as basic reference material for those learning English.”

“Naver pools its definitions from multiple dictionaries, most of which provide only literal, one-dimensional translations. Only a part of the example sentences (intended to show how a particular English term is used) are taken from reliable sources, while most of the English phrases have not even been translated into Korean,” Nam said.

He also cautioned users to avoid Naver’s crowdsourced dictionaries including the firm’s own Open Dictionary, as the definitions they carry are unverified.

The professor added that Naver “lacks a clear philosophy” in how it runs its dictionary platform, and urged the company to adopt more rigorous guidelines for its English-Korean dictionary.

By Sohn Ji-young (jys@heraldcorp.com)

Paul Kerry contributed to this article. — Ed.